You Can’t Blame Them for Trying

Earlier this month, Ohio voters considered a ballot initiative aimed at controlling the escalating spending on prescription drugs. It’s a concern felt in every state, including Colorado, and consumers and policymakers are desperately searching for a solution.

The Ohio proposal would require the state’s government, including its Medicaid agency, to pay no more than what the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) pays for prescription drugs. By federal law, the VA receives a 24 percent discount on drug prices.

Ohio voters resoundingly rejected the ballot initiative by a 79 to 21 percent margin.

Drug prices in the cross hairs

On the one hand, the Ohio ballot initiative might be a logical response to what many view as a perennial problem: high drug costs.

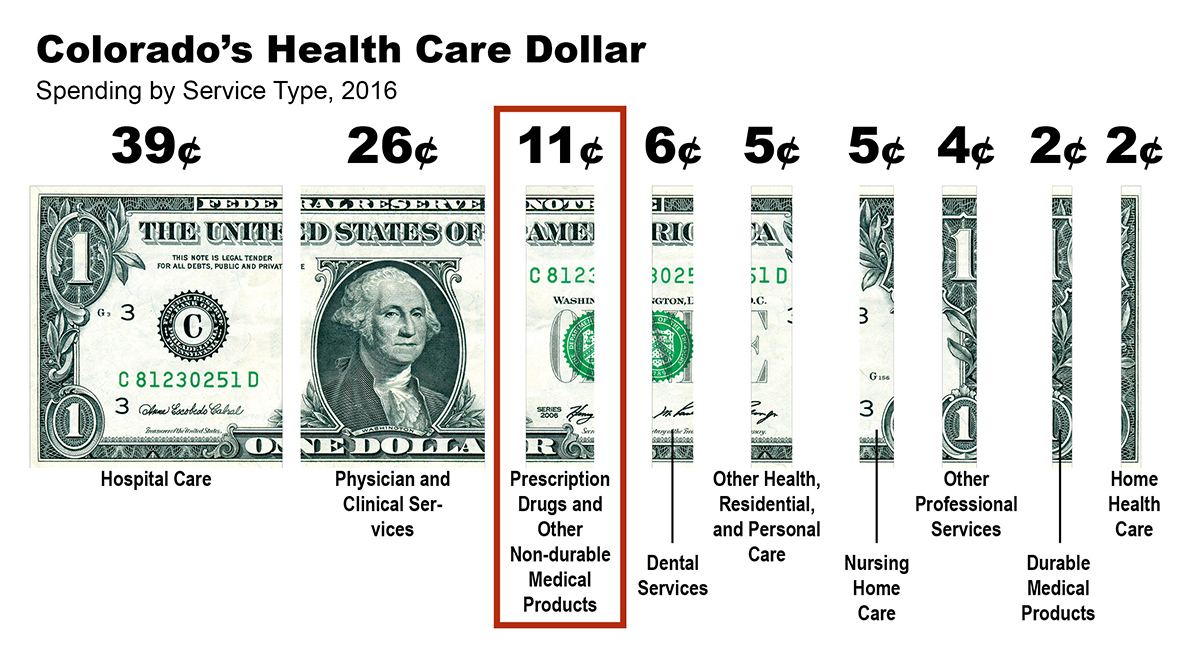

In Colorado, prescription drugs account for 11 percent of total health care spending, and that percentage is expected to grow faster than overall health care spending. Concerns about escalating prices led to a similar ballot initiative in California last year (it was defeated). Next year, voters in South Dakota and Washington, D.C. will decide similar proposals.

In Colorado, prescription drugs account for 11 percent of total health care spending, and that percentage is expected to grow faster than overall health care spending. Concerns about escalating prices led to a similar ballot initiative in California last year (it was defeated). Next year, voters in South Dakota and Washington, D.C. will decide similar proposals.

On the other hand, it is not surprising that the Ohio effort failed.

First, the ballot initiative unleashed an avalanche of spending to convince Buckeyes to vote “No.” The opponents benefited from a $58 million war chest compared with $17 million for the proponents, according to the Wall Street Journal and Ballotpedia. The combined total of $75 million made it the most expensive state initiative outside of California since at least 2006.

Second, voters seemed uncertain about whether the measure would actually work. Supporters argued that Ohio taxpayers would save $400 million per year in reduced drug spending. But opponents fueled skepticism, particularly a concern that drug companies would charge people with private health insurance or Medicare more to compensate for the price discounts offered to state agencies. In addition, Ohio’s nonpartisan Office of Budget and Management said it was unclear whether the measure would save money.

The outcome in Ohio is another example of the challenges of crafting health policy at the ballot box. We know something about that in Colorado, which just a year ago overwhelmingly rejected Amendment 69, which would have created a system of universal health care in our state.

Some might blame these failures on the big money that flows into ad campaigns. But we can’t ignore the fact there aren’t easy fixes to these complex problems. What looks like a straightforward fix —refusing to pay full price for drugs — inevitably creates broader impacts that are often hard to anticipate, much less quantify.

The desire to find fixes though the ballot box stems from the frustration that policymakers aren’t doing enough to solve problems in our health care system. I’m sympathetic to that viewpoint, yet it’s hard to see how such complex problems can be addressed in a process where deliberation takes place in 30-second ad spots. It’s worrisome that voters (or policymakers for that matter) were making decisions when there isn’t a reasonable sense of what the impacts would be. The cure could have been worse than the disease.

Regardless of your political leanings, Ohio’s “No” vote should be seen as a win for the idea that policy should be made with a credible understanding of its impacts, and that a more deliberative process is what’s needed to make real progress in improving our health care system.

Find CHI on Facebook and Twitter