The existence of resilience and protective factors, such as a strong sense of identity and social connectedness, is one possible explanation. These qualities may help safeguard mental health among non-white groups despite the barriers they face.

Protective factors play a crucial role in promoting good mental health, and they should not be overlooked as the state of Colorado makes a major investment in behavioral health in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Promoting these factors — through increased research and integration into public health and health care delivery settings — has the power to destigmatize mental health, address long-standing systemic barriers, build resilience, and improve well-being for all Coloradans.

A Look at Suicide Rates Among Communities of Color

Mental health stigma can lead to worse health outcomes for people of color. This is especially true when it is coupled with a multitude of systemic barriers to care, such as mistrust in health care providers, less access to insurance coverage, and a lack of culturally competent providers. See CHI’s report Stigma and Systemic Barriers: Why Mental Health Care Is Not the Same for Everyone for more on the barriers that people of color face.

But in Colorado, the age-adjusted suicide rate by race and ethnicity shows that Asian/Pacific Islander, Black/African American, and white-Hispanic groups have lower rates of death by suicide compared with non-Hispanic whites. This is true for both males and females. This is not the case for Native American and Indigenous populations, who experience the highest rates of suicide among all racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

Suicide data can be unreliable. Deaths by suicide among people of color are more likely to be misclassified compared with those of whites. Coroners might classify a suicide as a homicide or as an undetermined cause of death, or families might not want to record the accurate cause of death due to stigma. However, many believe these lower rates cannot be attributed solely to misclassification of deaths; instead, they point to resilience and powerful protective factors among people of color.

Resilience, Protective Factors Bolster Mental Health

Resilience is the ability to adapt when facing tragedy, trauma, or other stress. It can protect people from developing some mental health conditions and improve the coping ability of those with existing conditions.

Resilience is not “toughness” and it’s not a trait that people simply have or don’t have. Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child describes resilience as the result of a combination of protective factors — individual or environmental characteristics, conditions, or behaviors that reduce the effects of stressful life events. This can include, for example, problem-solving skills or strong social connectedness. As a result, resilience can be built at any age, though childhood and youth can be particularly formative years.

Resilience, recovery, and well-being are also deeply cultural concepts, writes Leslye Steptoe of the Mental Health Center of Denver. For many people of color, resilience may be inherent due to the historic and ongoing trauma that they and their families have faced. Resilience is needed to survive. And in combination with powerful protective factors that exist in these communities, it may bolster mental health.

“For Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC), generations of trauma, systemic racism, and cultural barriers lead to resilience looking very different than what we have taken it to mean in our society. This is not to say that we should discard resilience. In fact, I would say we should pay more attention to it. While resilience can be developed, we should consider how some have no choice but to be resilient.”

— Gustavo A. Molinar; Mental Health America; (Re)Defining Resilience: A Perspective of ‘Toughness’ in BIPOC Communities

Protective Factors in Practice

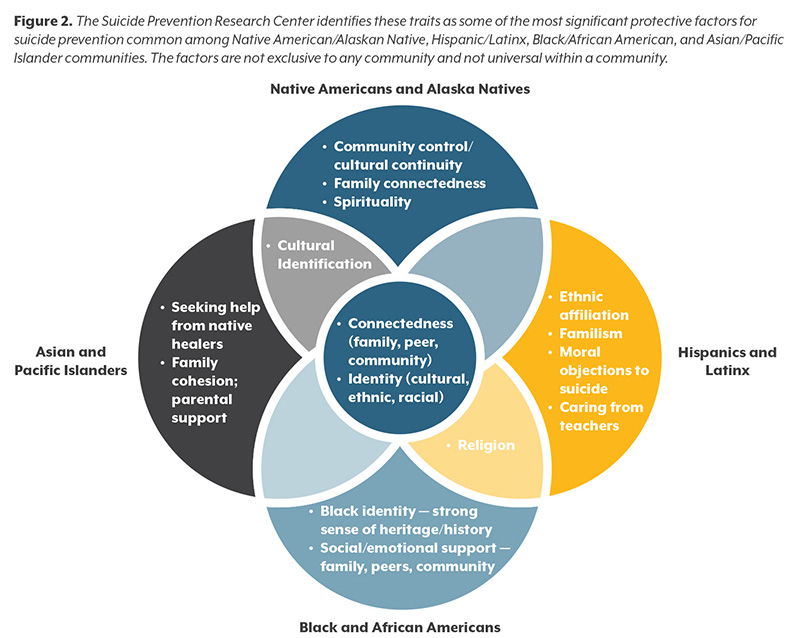

Effective mental health care, connectedness, problem-solving skills, and contacts with caregivers are protective factors that have been shown to be significant across all racial and ethnic populations. But other protective factors specific and significant to non-white racial and ethnic groups also exist. Figure 2 shows these commonly identified protective factors among different communities of color as outlined by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

Providers, policymakers, and others need to understand how these protective factors can build resilience and safeguard mental health. The benefits of this are twofold: Protective factors are critical to ensuring positive outcomes for youth and encourage resilience-building throughout critical formative years; and the lack of certain protective factors, for example strong social connectedness, can exacerbate mental health stressors, such as increased social isolation.

With increasing mental health needs due to COVID-19 alongside ongoing efforts to reform Colorado’s behavioral health system, there is a key opportunity at hand to rethink how to best integrate these factors to build resilience and to better tailor mental health awareness, treatment, and intervention programs.