The Competition Conundrum

CHI Analysis Shows Uncompetitive Markets for Hospitals and Insurance Throughout Colorado

Key Takeaways

- Colorado counties with the least competition among both hospitals and insurance carriers have the state’s highest insurance premiums, according to a new Colorado Health Institute analysis.

- The low-competition, high-premium counties are in rural and mountain areas, where market conditions make it difficult to increase competition.

- One-size-fits-all policy solutions won’t be effective.

The chronically high cost of health insurance has drawn ongoing attention from the Colorado Division of Insurance, the governor’s office, rural lawmakers — and, of course, Coloradans who pay the high premiums.

Policymakers often point to a lack of competition among hospitals and insurers as a driver of high costs. But there has been little analysis of the relationship between competition and the price of health insurance in Colorado.

The Colorado Health Institute (CHI), recognizing the need for information to support policy solutions, created the CHI Competition Matrix to analyze hospital and insurance carrier competition in the individual market in each Colorado county and assess competition’s relationship with insurance premiums.

The matrix reveals a correlation between low levels of hospital and insurer competition and high health insurance prices. (See Figure 1.)

Thirteen counties have low levels of competition in both their hospital and carrier markets. Most also have the state’s highest premiums. They are rural counties spread throughout the state, but especially on the Western Slope. Conversely, counties with relatively higher levels of competition have lower premiums. Most Front Range counties are in this category.

This is consistent with the economic theory that greater competition in both hospital and insurance markets can help put a check on the price of insurance.

While the CHI Competition Matrix shows that low competition is strongly associated with high premiums in Colorado, policy solutions targeting competition alone won’t be enough. Other factors influence insurance prices as well.

Rural areas, for example, have fewer residents than urban areas. This can make it difficult for carriers to manage their financial risk and lead to higher insurance prices.

Because of the complexity of these markets and variations across Colorado, it’s clear that solving the state’s competition conundrum won’t be a one-size-fits-all exercise.

What the CHI Competition Matrix Tells Us: Lower Competition, Higher Premiums

A clear trend emerges from the CHI Competition Matrix: Insurance premiums are correlated with the level of competition among both hospitals and insurance carriers.

Sixteen counties had the highest premium for a single 40-year-old, about $700 per month. (Prices are for the second-lowest-cost silver plan offered through Connect for Health Colorado, the state’s online insurance marketplace.) Eleven of these counties — Archuleta, Dolores, Gunnison, Hinsdale, Jackson, Lake, Moffat, Montezuma, Pitkin, San Juan, and San Miguel — also have low levels of both hospital and carrier competition. These counties are found in the upper left corner of the matrix.

The correlation isn’t perfect. Five counties with the most expensive premiums — Delta, La Plata, Montrose, Ouray, and Rio Blanco — have medium competition in either their hospital or carrier markets.

In contrast, counties with the lowest premiums, about $408 per month, generally have higher levels of hospital and carrier competition.

The trends shown in the Competition Matrix are consistent with the economic theory that the lack of competition can lead to higher consumer prices. A market with only one hospital has more leverage over insurance carriers to negotiate higher hospital service prices, and that can translate into higher insurance premiums for consumers. Similarly, an insurance carrier that faces no competition from other carriers won’t experience as much pressure to hold down premiums in order to attract customers.

Rural Areas: Challenging Market Conditions, No Easy Answers

So does it stand to reason that Colorado should just pump up the number of hospitals and insurance carriers to address high insurance premiums?

A closer look at the trends in Colorado’s urban and rural communities shows it’s not that simple.

In general, rural areas have low levels of both hospital and carrier competition.

Counties with low levels of hospital and carrier competition are located across the Western Slope, including Moffat and Routt counties in the northwest corner of the state, Pitkin and Gunnison counties in the central mountains, and Dolores and Montezuma counties in the southwest corner (see Maps 1 and 2).

High insurance premiums in rural counties are likely driven by more than the lack of competition.

Operating a hospital in a sparsely populated area comes with special challenges. For example, small populations mean that hospitals can’t spread their fixed costs across a large volume of patients, which can raise the average cost of caring for a patient and drive up insurance premiums.

Insurance carriers in rural Colorado also face difficulties. The individual market is risky for carriers. Customers frequently cycle on and off insurance as their financial or employment circumstances change. Customers in this market also tend to be very sensitive to the price of insurance and will readily switch plans to get a cheaper price. This “churn” creates uncertainty and makes it difficult for insurers to predict how much medical care their customers will need.

Small populations compound the impact of high churn rates. A handful of customers who have unexpectedly high medical costs can influence whether a carrier makes or loses money in a rural area.

Combined, these factors make it so difficult for insurers to manage risk that many simply avoid small rural markets. For example, 14 counties currently have only one carrier on the individual market (Anthem). Other carriers may charge higher premiums to account for this unpredictability.

Colorado’s Urban Markets: More Competition, But Still Room for Improvement

The level of both hospital and insurance competition in Colorado’s urban areas is generally higher than in rural regions. However, no county in Colorado has a hospital or carrier market that would be considered competitive under guidelines used by the U.S. Department of Justice.(1) This is consistent with other studies that show hospital and carrier markets across the nation’s urban areas often lack vigorous competition.(2,3)

The factors that hamper competition in urban areas differ from those in rural regions.

Cities have experienced a wave of hospital consolidations. While there are 24 hospitals in the Denver area, 20 are owned by one of four large hospital systems: Centura Health, HealthONE, SCL Health, or UCHealth. Hospitals within the same system are not direct competitors.

Urban areas also have more insurance carriers than rural areas, but that doesn’t necessarily lead to vigorous competition. Front Range counties typically have four or five carriers that offer plans on the state’s insurance exchange, but those markets are dominated by one or two carriers. In the Denver metropolitan area, Kaiser Permanente and Cigna account for about 75 percent of enrollment on the insurance exchange, which calls into question whether competition is thriving in those insurance markets.

Options to Improve Competition and Market Conditions

Because there is no single cause behind the problem of Colorado’s uncompetitive markets, there is no one solution. Policymakers should instead consider a variety of options to improve competition, tailoring solutions to address regional circumstances.

Option One: Reduce Risks for Insurance Carriers

A major barrier to greater competition in the individual market is that carriers face significant business risk. One approach to reducing risk is reinsurance, which can limit the amount of loss an insurance company incurs and lead to lower premiums.

Minnesota and Alaska have created reinsurance programs, which leverage state-run funding to cover the highest-cost claims. In Colorado, the 2019 legislature passed a reinsurance bill designed to reduce individual market premiums by as much as 35 percent in some areas of the state.(4)

A second approach to reducing risk is to reduce excess churn — consumers cycling on and off health plans — by tightening enrollment rules in the individual market. Insurers say that some churn is due to people enrolling only when they get sick and then discontinuing their coverage after they receive care.

Colorado limits insurance plan purchases to the annual open enrollment season, which runs from November to January. But there are many exemptions to the rule, and tightening them would help insurers more accurately predict their costs, possibly leading to more insurance companies offering plans.(5)

Option Two: Increase Health Insurance Options

Colorado could reconsider whether to require insurance carriers to expand to rural areas that currently have little competition. This approach would be difficult. Insurers might resist offering plans in counties where they think they will lose money.

In the past few years, the legislature rejected proposals that would have required carriers that offer health benefits to state employees to also sell individual market plans through Connect for Health Colorado. The 2019 legislature considered a program based on this concept in Senate Bill 19-004, but this provision did not pass.

Another proposal is a state “buy-in” option. This would allow people who don’t qualify for Medicaid to buy coverage through the program. The premiums could be lower than those available on the individual market, potentially drawing more customers and injecting more competition. The 2019 legislature passed House Bill 19-1004, which calls on state agencies to develop a detailed proposal to allow people to buy in to public coverage.(6)

A risk, however, is that the few remaining private insurance carriers might leave the market in some areas rather than compete against Medicaid. Medicaid reimburses providers at rates lower than those paid by private insurance carriers, and private carriers could view this as an unfair competitive advantage.

Option Three: Increase Oversight of Insurance Carriers and Health Care Providers

State regulators can play an important role by providing oversight of mergers and acquisitions that reduce competition among hospitals, physician groups, and insurance carriers.(7,8,9)

For example, Colorado joined a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit to block Anthem’s proposed acquisition of another major insurance carrier, Cigna.(10) The acquisition was scuttled in 2017 by a federal court that cited its potential anticompetitive effects.

Some states have taken measures to combat consolidation among providers. For example, Idaho’s attorney general joined a successful challenge blocking St. Luke’s Health System’s proposal to acquire a large physician group.(11,12)

Colorado’s attorney general and Division of Insurance could take a more active approach to challenging consolidation in health care markets to encourage competition.

Option Four: Encourage New Models of Health Care

Location matters when it comes to health care. A provider in Lamar, for example, is unlikely to compete with a provider in far-away Durango. However, telehealth eliminates geographic boundaries and can foster competition across communities. For example, a primary care physician could refer a patient to a specialist via telehealth instead of making a referral to the local hospital. A carrier could also encourage its members to seek telehealth services. This could reduce the negotiating power of local providers and could translate into lower insurance premiums.

Colorado has made strides to encourage the adoption of telehealth, such as passing a bill in 2018 to pay for better broadband access in rural areas. Nevertheless, it will take time for providers, carriers, and patients to make telehealth a routine part of the health care delivery system.

Conclusion

The high price of insurance on the individual market is a vexing problem without a simple solution. And yet affordable health insurance increases access to care and is a key to a healthier Colorado.

CHI’s Competition Matrix shows a clear relationship between low levels of insurance and hospital competition and high insurance prices. However, CHI’s research finds a nuanced relationship between competition and premium prices: Competition is important, but so are other market challenges that exist in many rural areas.

Policymakers interested in increasing competition as a means of lowering prices could consider taking steps to reduce risks for insurance carriers, increase health insurance options, increase oversight of insurance carriers and health care providers, or encourage new models of care –– or some combination of those options.

Appendix: Methods for Creating the CHI Competition Matrix

We measured competition using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a standard method of examining competition widely accepted by economists and the federal government. The HHI considers the number of competing businesses as well as their market shares.

If a market has just one business, that business has a monopoly and can exert market power — the ability to raise prices without the fear of being undercut by a competitor. A monopoly market has the maximum HHI value of 10,000.

Markets with more competition have lower HHI values. For example, a market with five businesses that each have a 20 percent market share has an HHI value of 2,000.

This is a step-by-step guide to how CHI conducted the analysis:

1. Define Hospital Markets

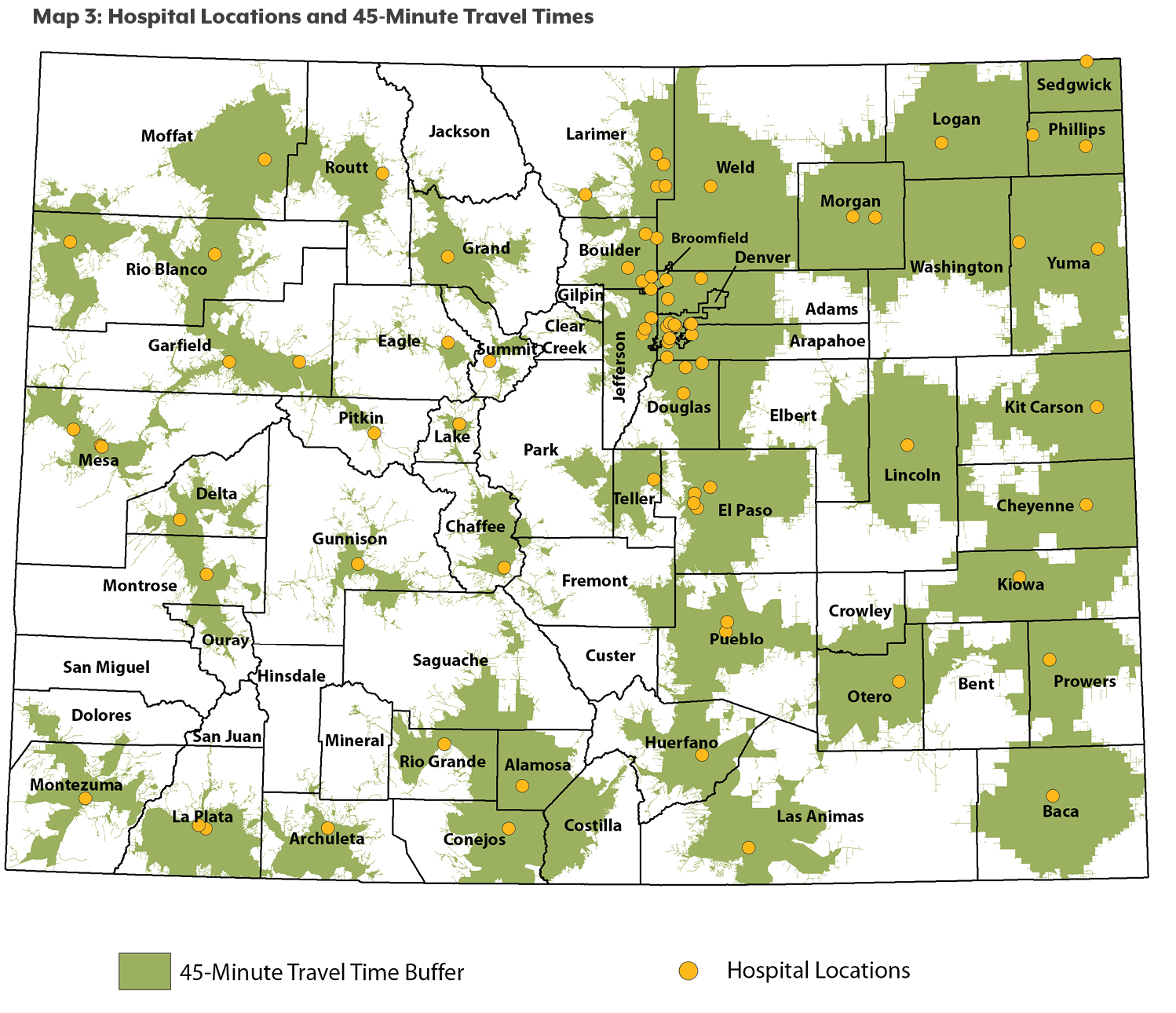

We placed a hospital in a county’s market if it is within a 45-minute drive of any part of that county.(13) In this methodology, a single hospital can be part of the market in more than one county. Eighteen of Colorado’s 64 counties don’t have a hospital within their borders, but there is at least one hospital within a 45-minute drive. (See Map 3).

CHI estimates that less than one percent of Coloradans — fewer than 56,000 residents — don’t have a hospital within a 45-minute drive.

2. Measure Hospital Market Share

Market share is based on the number of annual patient discharges at each hospital.(14) When multiple hospitals are part of a single hospital system, they are treated as a single hospital. This is because a system’s individual hospitals are unlikely to compete with each other in pricing their services.

3. Calculate Hospital HHI Values

We calculated each county’s hospital HHI value and placed them in one of three hospital competition categories:(15)

• High competition: Counties with an HHI value up to 3,500.

• Medium competition: Counties with an HHI value between 3,501 and 7,000.

• Low competition: Counties with an HHI value between 7,001 and 10,000.

We chose these categories so that about half of the counties would fall into the medium competition category. In addition, these cutoffs coincide with relatively large gaps in HHI values.

The competition categories only represent relative differences among counties. Counties in the “high competition” category have a more competitive market than other counties, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that there is enough competition to keep prices in check.(16)

4. Calculate Insurance Carrier HHI Values

We looked at county insurance markets based on the number of carriers that offer individual market plans through Connect for Health Colorado, the state-based insurance exchange.(17)

This method captures only a minority of the insurance market, but we did this for two reasons: Individual market premiums have been rising the fastest, and data are available at a county level. Only about 173,000 Coloradans are enrolled in these plans, but this market serves as a good starting point to analyze insurance competition.

We placed each county into one of three categories for insurance carrier competition:

• High competition: Counties with an HHI value up to 4,800.

• Medium competition: Counties with an HHI value between 4,801 and 8,400.

• Low competition: Counties with an HHI value between 8,401 and 10,000.

As with hospitals, these HHI cutoffs were selected so that about half of Colorado counties were categorized as having a medium level of insurance competition.

5. Measure Insurance Premiums

Premiums are based on the second-lowest-cost silver plan available to a 40-year-old resident in 2018. Silver plans account for approximately 45 percent of enrollments (18) and serve as the benchmark for calculating federal tax credits.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission. Horizontal Merger Guidelines. August 19, 2010. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/atr/horizontal-merger-guidelines-08192010#5c.

² Fulton BD. “Health care market concentration trends in the United States: evidence and policy responses.” Health Affairs. 2017;36(9):1530-38.

³ American Medical Association. “Competition in Health Insurance Markets: A Comprehensive Study of U.S. Markets. 2016 Update.”

4 Colorado General Assembly. House Bill 19-1168, State Innovation Waiver Insurance Program.

5 Turner GM. “ACA rules allow people to game the system, contributing to premium spikes.” Forbes. June 11, 2016.

6 Colorado Health Institute. “Public Option, Pressing Questions,” February 2019.

7 Ingold J. “In Colorado’s drumbeat of medical mergers, rural hospitals often trade independence for better care,” Denver Post, July 4, 2017.

8 Sealover E. “Merger creates metro Denver’s largest group of primary-care doctors,” Denver Business Journal, November 23, 2015.

9 Rodgers J. “UCHealth acquires Integrity Urgent Care in Colorado Springs,” Colorado Springs Gazette, July 18, 2016.

10 U.S. Department of Justice. “Justice Department and State Attorneys General Sue to Block Anthem’s Acquisition of Cigna, Aetna’s Acquisition of Humana,” Press release, July 21, 2016.

11 Singer T. “New Health Care Symposium: Unpacking the issues of vertical and horizontal consolidation—the St. Luke’s case.” Health Affairs blog, March 3, 2016.

12 U.S. Federal Trade Commission. St. Luke’s Health System, Ltd. and Saltzer Medical Group, P.A., updated May 2, 2017, available at: https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/cases-proceedings/121-0069/st-lukes-hea….

13 We included only acute and critical access hospitals. We conducted sensitivity analyses using 30- and 60-minute drive radiuses and found that the relationship between the degree of competition and premiums was not sensitive to the drive-time assumption.

14 We obtained discharge data from the 2015 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) hospital cost reports.

15 We calculated county HHI values by first calculating HHI values for each census tract in a county. We aggregated the census tract HHIs to the county level using a “crosswalk” file developed by the University of Missouri, which based its crosswalk on population data from the American Community Survey. Crosswalk files estimate the relationship between two or more overlapping geographic areas, such as the percentage of a county population that lives in a certain census tract.

16 For example, markets with HHI levels above 2,500 are generally considered as “highly concentrated” with little competition, according to federal guidelines used to evaluate the competitive effects of potential business mergers. The guidelines also say that markets with HHI values below 1,500 are “unconcentrated,” and companies are unlikely to be able to exert market power. See U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission. Horizontal Merger Guidelines. August 19, 2010. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/atr/horizontal-merger-guidelines-08192010#5c.

17 We obtained data from Connect for Health Colorado on the number of effectuated plans per carrier per county as of July 18, 2018.

18 Connect for Health Colorado. “By the Numbers: Open Enrollment Report Plan Year 2018."