Increasing Coverage, Lingering Barriers

Key Takeaways

- Black and African-American Coloradans achieved parity in health insurance coverage with the rest of the state after the Affordable Care Act took effect.

- A larger share of black and African-American Coloradans reported that they were in excellent, very good or good health after 2014, and a smaller share reported cost as a barrier to seeing a doctor.

- These groups visited emergency rooms for non-emergency reasons more and saw doctors and specialists less than other Coloradans. More cited transportation as a barrier to receiving care than other Coloradans.

That’s according to the first in-depth examination of data from the Colorado Health Access Survey, or CHAS, on black and African-American Coloradans’ health care access and experiences.

On the national level, health care disparities that affect black and African-American Coloradans are well-documented.1 Studies show these groups receive lower quality care and less of it, and therefore experience worse health outcomes than white Americans.2, 3

But the CHAS points to a significant improvement in both insurance coverage and health among the state’s black and African-American residents between 2011 and 2017.

Insurance Status

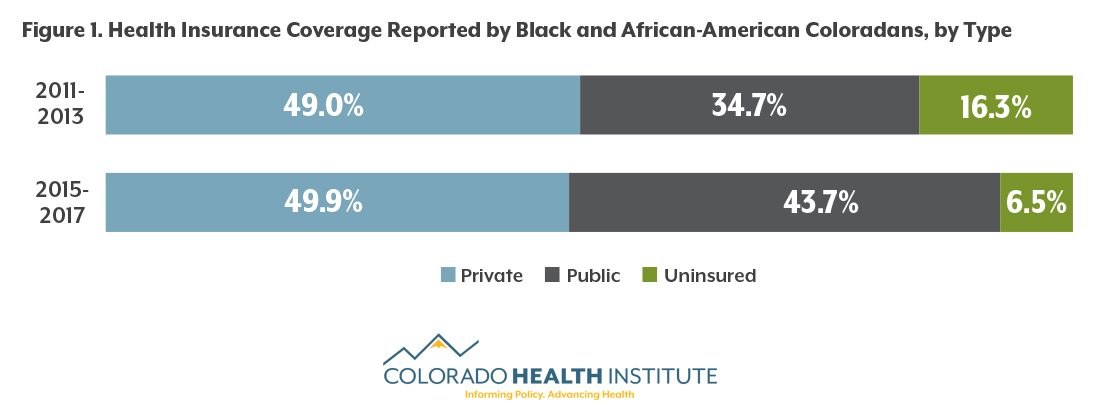

The share of black and African-American Coloradans who report being uninsured decreased by almost 10 percentage points after full implementation of the ACA. In 2011-13, according to the CHAS, more than 16 percent were uninsured. That was slightly higher than the rate for the state as a whole, 14.8 percent. In 2015-17, 6.5 percent of black and African-American Coloradans were uninsured, the same as the statewide rate.

Most of the decrease came from the expansion of Medicaid in 2014, which allowed adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty line to enroll in public insurance. Approximately 35 percent of black and African-American Coloradans were insured through public insurance before the ACA, compared with 44 percent post-ACA. During this time, there was essentially no change in private insurance coverage.

Research shows that people without health insurance receive less medical care, have worse health outcomes, and face a financial burden when forced to seek care without insurance.4

Access to Health Care

Although insurance may open the door for people to get care, it does not guarantee that they receive services and treatment.

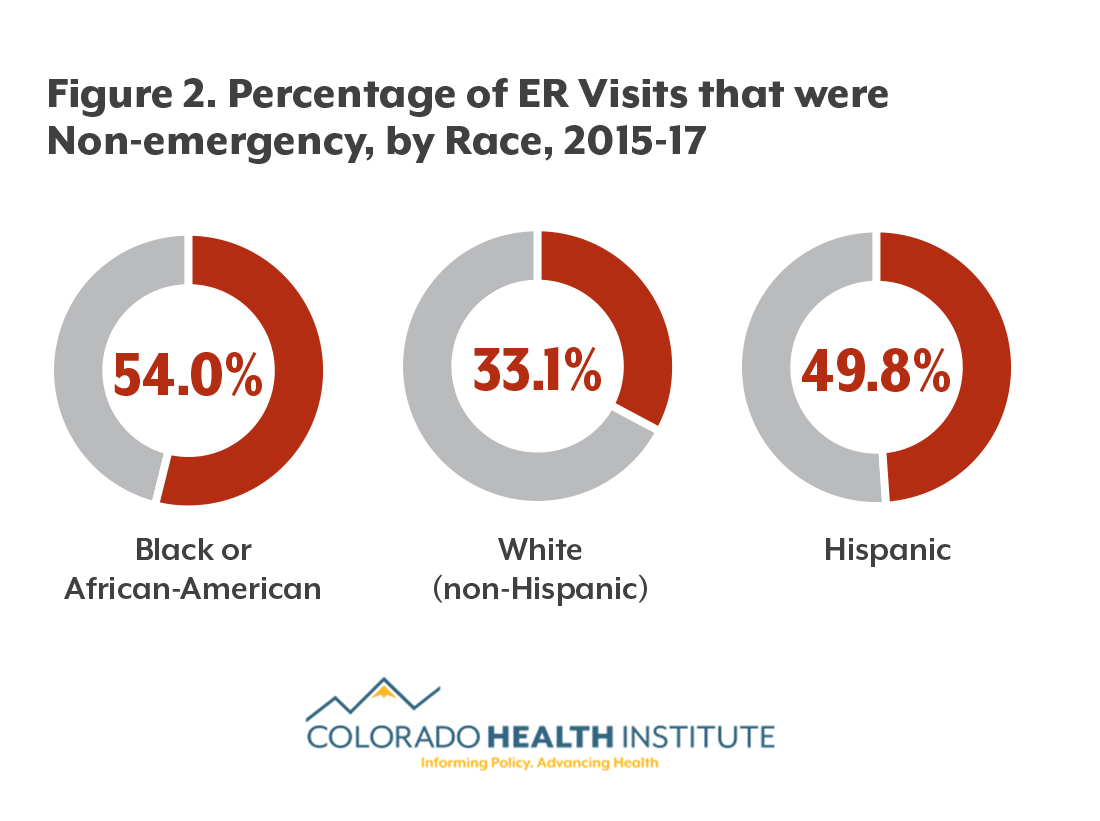

Despite having an uninsured rate equal to other Coloradans’, black and African-American Coloradans were less likely to report seeing doctors and specialists in the previous year and more likely to visit the emergency room for non-emergency reasons than other Coloradans after the ACA, the CHAS analysis showed. More than one in three people who identified as black or African American report not having gone to the doctor in the previous year, compared with one in four other Coloradans.

However, black and African-American Coloradans report having a usual source of care on par with the state average, around 86 percent. Having a usual source of care indicates that people know where to go for primary or preventive care.

Barriers Remain

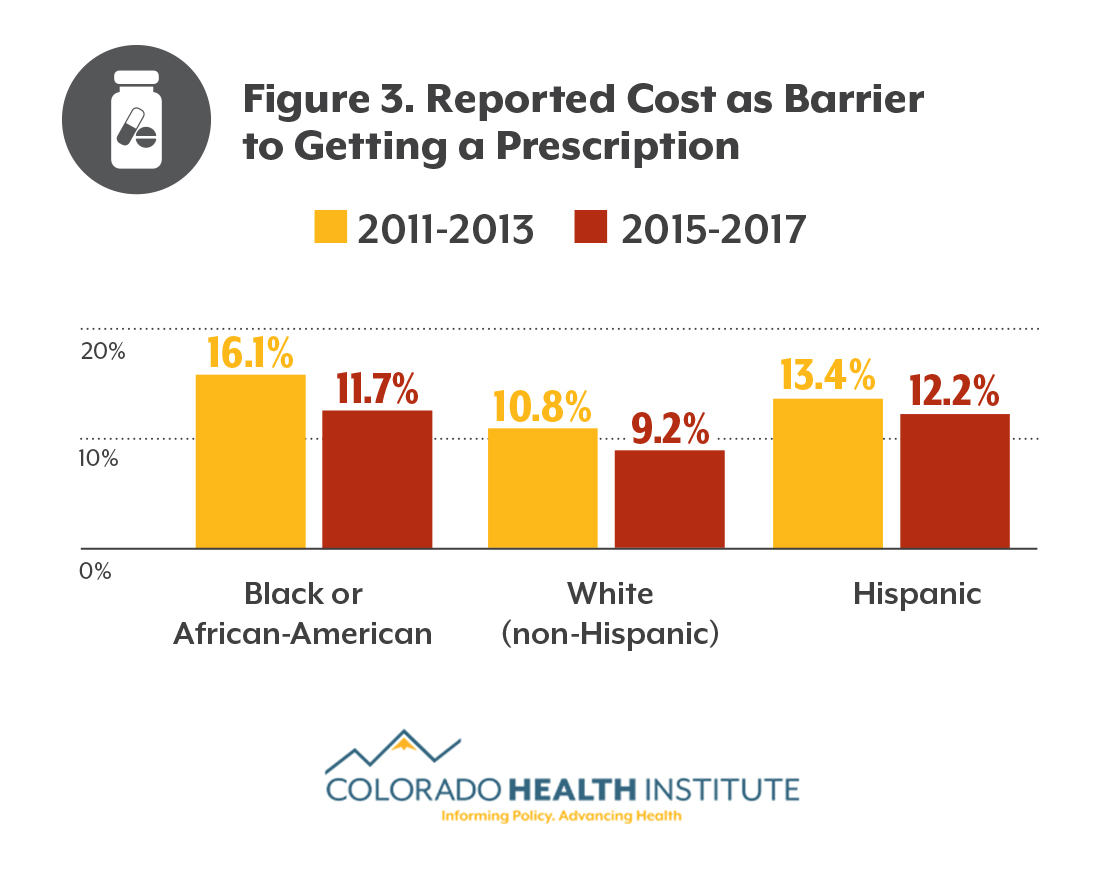

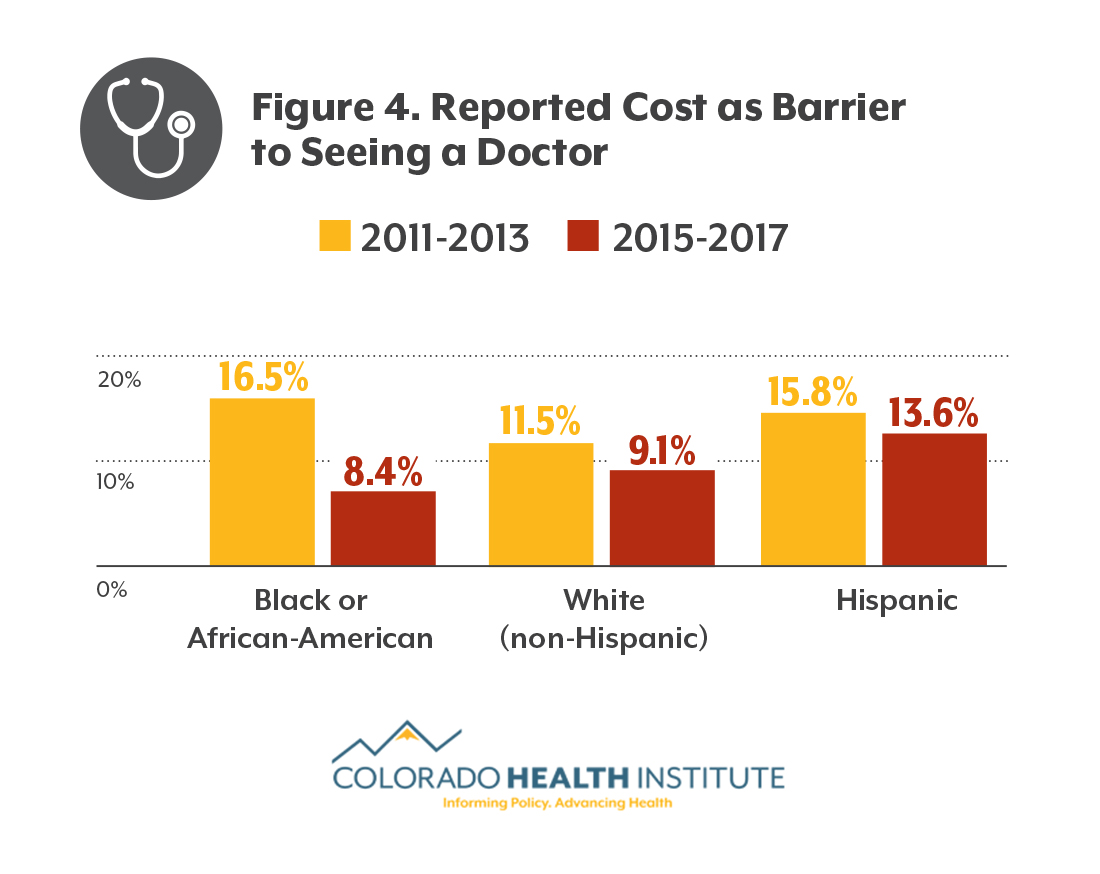

In general, the ACA appears to have improved access to care. For example, a smaller portion of those who identified as black or African American cited cost as a barrier to care after the ACA than before, as did other Coloradans, according to CHAS data. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

After the ACA, fewer black and African-American Coloradans reported that cost was a barrier to getting prescriptions, though they were still more likely to cite cost than white Coloradans. After the ACA, about the same percentage of African-Americans and white Coloradans reported that cost prevented them from seeing a doctor.

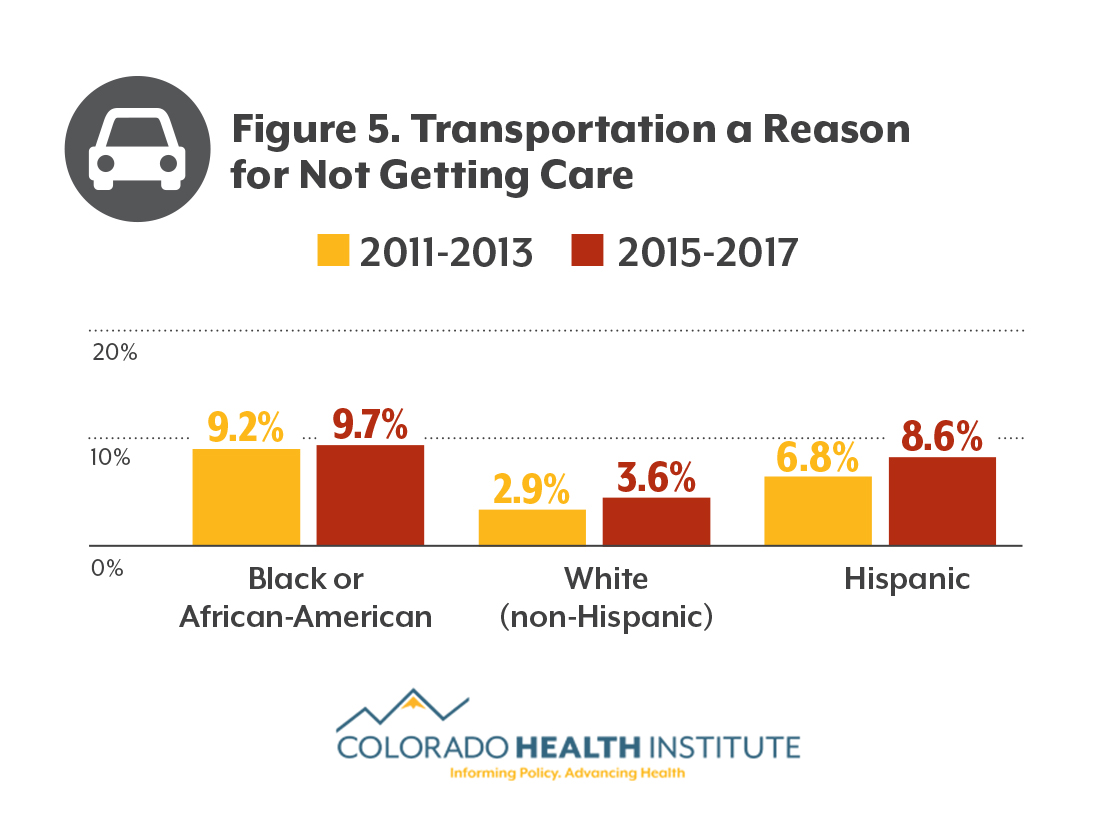

Transportation remains a barrier to health care for black and African-American Coloradans. Nearly one in 10 reported not getting care because of a transportation challenge, nearly double the state average.

A combination of factors, including income, insurance status, geography and transportation policies, influence a person’s ability to access transportation to health care.

Health Outcomes

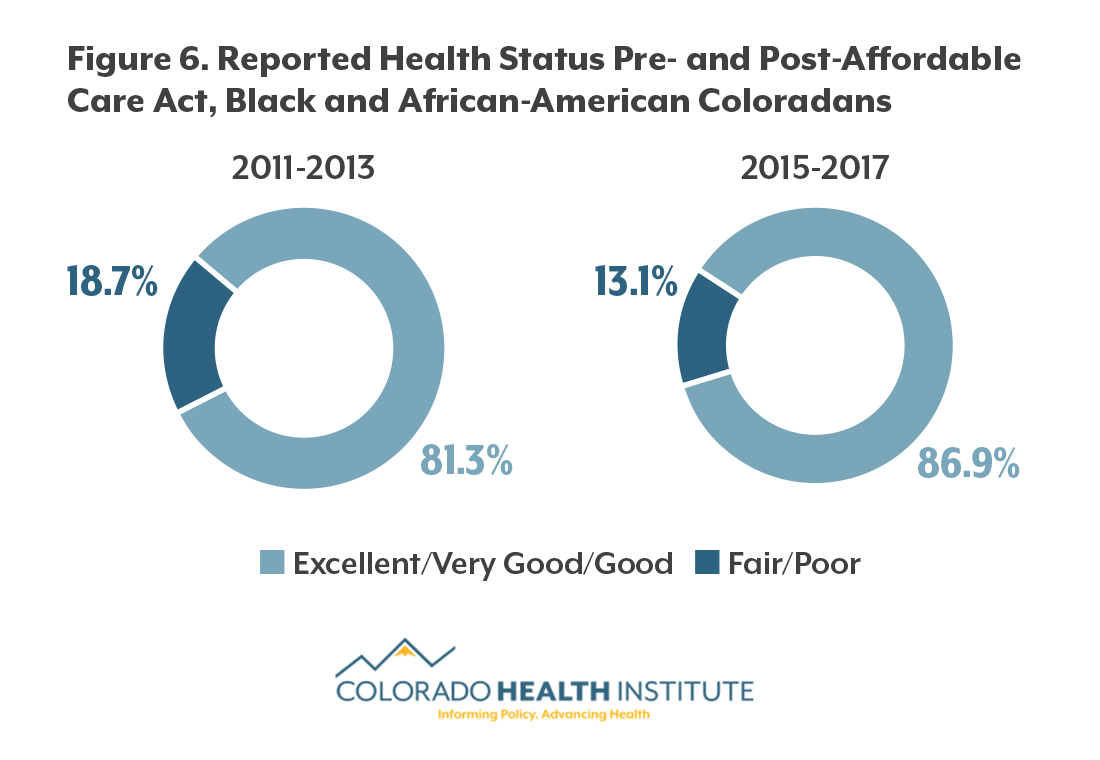

Despite having some differences in access and barriers to care, black and African-American Coloradans reported having either excellent, very good or good health at a rate on par with the rest of Colorado in 2015-17 — approximately eight in nine for both populations. The same goes for mental health, with about 90 percent of both black and African-Americans and other Coloradans reporting good mental health.

A higher proportion of black and African-American Coloradans reported good general health after the implementation of the ACA than before it (87 percent versus 81 percent).

The ACA, and the large numbers of black and African Americans covered by the expansion of Medicaid, could be part of the reason why there is an improvement in reported health status.

Conclusion

This first-ever analysis of black and African Americans’ responses to the CHAS reveals landmark improvements in insurance coverage and affordability. In the most recent surveys, black and African-American Coloradans were insured at much higher rates, were less likely to say cost is a barrier to care, and reported good health at similar rates to the rest of Colorado.

Future efforts to address non-emergency ER visits and reduce barriers to care like cost and transportation may help more black and African Americans access the care they need.

Creating a Direct Line to Health Data

Reliable health data on Colorado’s black and African-American communities has been hard to find.

“What’s going on with the African-American population, regardless of age – it was just never available,” said Deidre Johnson, executive director of the Denver-based Center for African American Health, a nonprofit that focuses on the health of black and African Americans in Colorado. “We know when it comes to things like asthma and cardiovascular disease, we have health disparities across the board. At the same time, there’s very little authentic information about us.”

Johnson said this new CHAS analysis helps “fill a persistent and important gap.”

But the Center for African American Health is also taking steps to fill that gap.

In May 2017, it created a regularly administered survey called BeHeard Mile High. More than 1,200 people, most of them black or African American, receive occasional “micro surveys” of 10 questions or less via email, text or mail.

A health survey that reached out to African-Americans in Colorado through churches was an inspiration for Johnson. Similar surveys by health organizations usually have trouble getting even a few hundred people to respond, but this church-based survey reached nearly 2,000 respondents.

“I have always believed it matters who’s asking the questions,” Johnson said. “And I was tired of secondhand data.”

The Center for African American Health has been building its respondent panel at community and health events. Johnson hopes to eventually have 3,000 participants.

So far, BeHeard Mile High has collected information on transportation and other issues that affect access to health care. While the initiative is in its early stages, the data informs the work of the Center for African-American Health and other organizations.

Meanwhile, Johnson’s group is working on a spectrum of issues, ranging from protecting gains in insurance coverage to reducing barriers to care to culturally responsive care.

In 2018, that work includes more offerings for children, youth, and families, she said. “We have to do what we can to make sure kids have opportunities to be as healthy as possible.”

The Importance of Cultural Context

Disparities in medical treatment and health outcomes between black and African Americans and white Americans are widely documented in the medical literature. Often, these national studies are done by taking a closer look at medical records (such a physician’s recommendations, treatments received, diagnosis rates and fatality rates) of large numbers of people and then breaking the data down by race to see if there are differences.

The CHAS does not take a deep dive into clinical treatments. It does, however, ask respondents to report their health status as either excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. It is important to note that this answer is subjective, and that saying black and African Americans are reporting equally good health as other Coloradans doesn’t mean there are no gaps in health outcomes.

The benchmark for “good health” for one community might be different than it is for others. Further investigation would be necessary to confirm that African-Americans are enjoying the same level of good health as other Coloradans.

About the CHAS and data on Black and African-American Coloradans

The CHAS has been collecting data on Coloradans’ insurance status, access to health care and use of the health care system since 2009. This survey is administered to 10,000 Colorado households every other year.5 Black and African-American Coloradans make up only 4.5 percent of the state’s population, resulting in small CHAS samples that did not allow for detailed analysis.6

To work around this issue, CHI weighted and aggregated the data from survey years, creating two categories: pre-ACA (2011 and 2013) and post-ACA (2015 and 2017). The ACA’s major provisions took effect in 2014. This technique allowed for comparison between those who identified as black or African American and the state average and the ability to investigate trends over time.