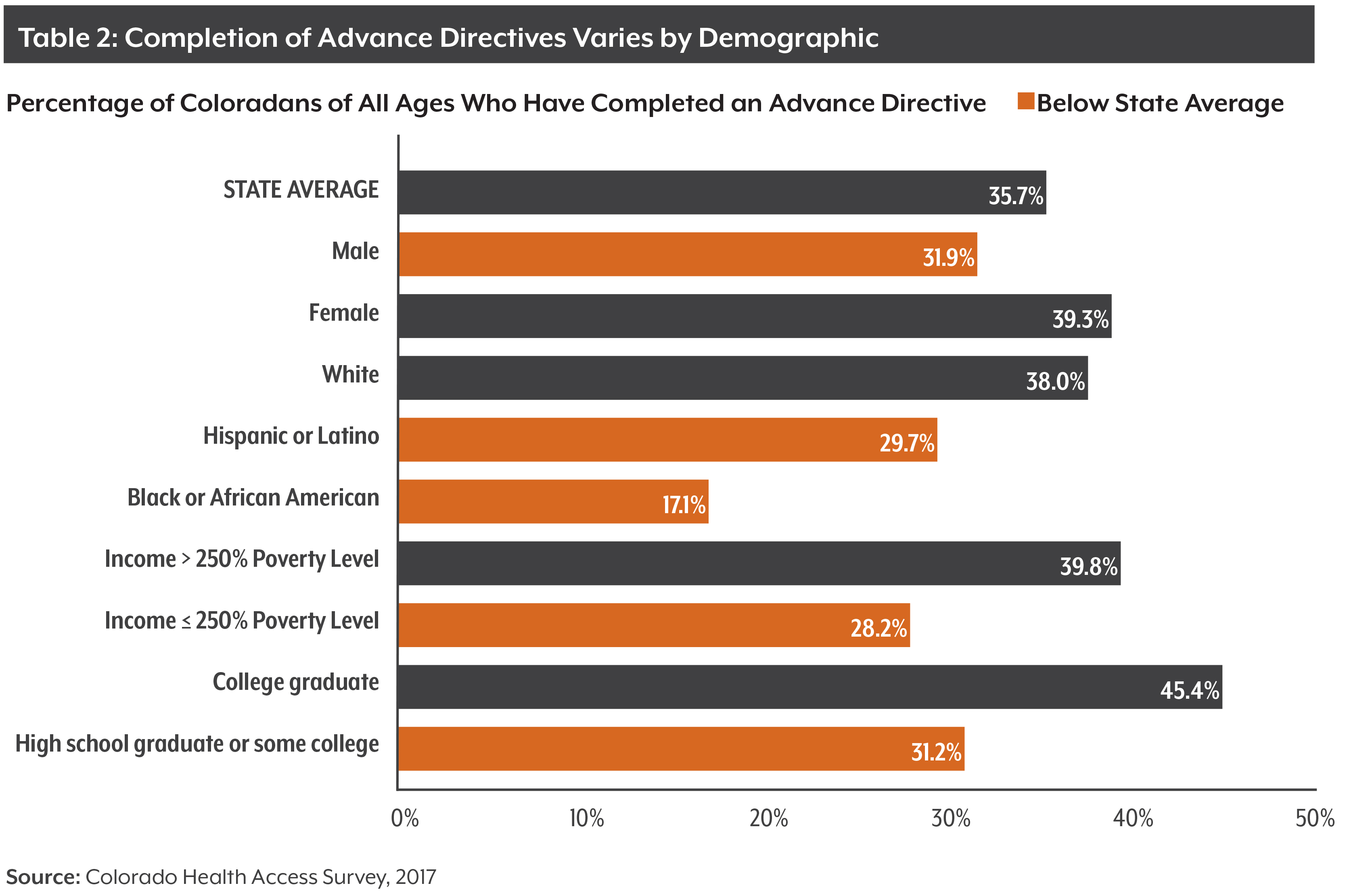

Nearly a quarter million Coloradans are facing their retirement years without an advance directive to help ensure their end-of-life wishes will be honored.

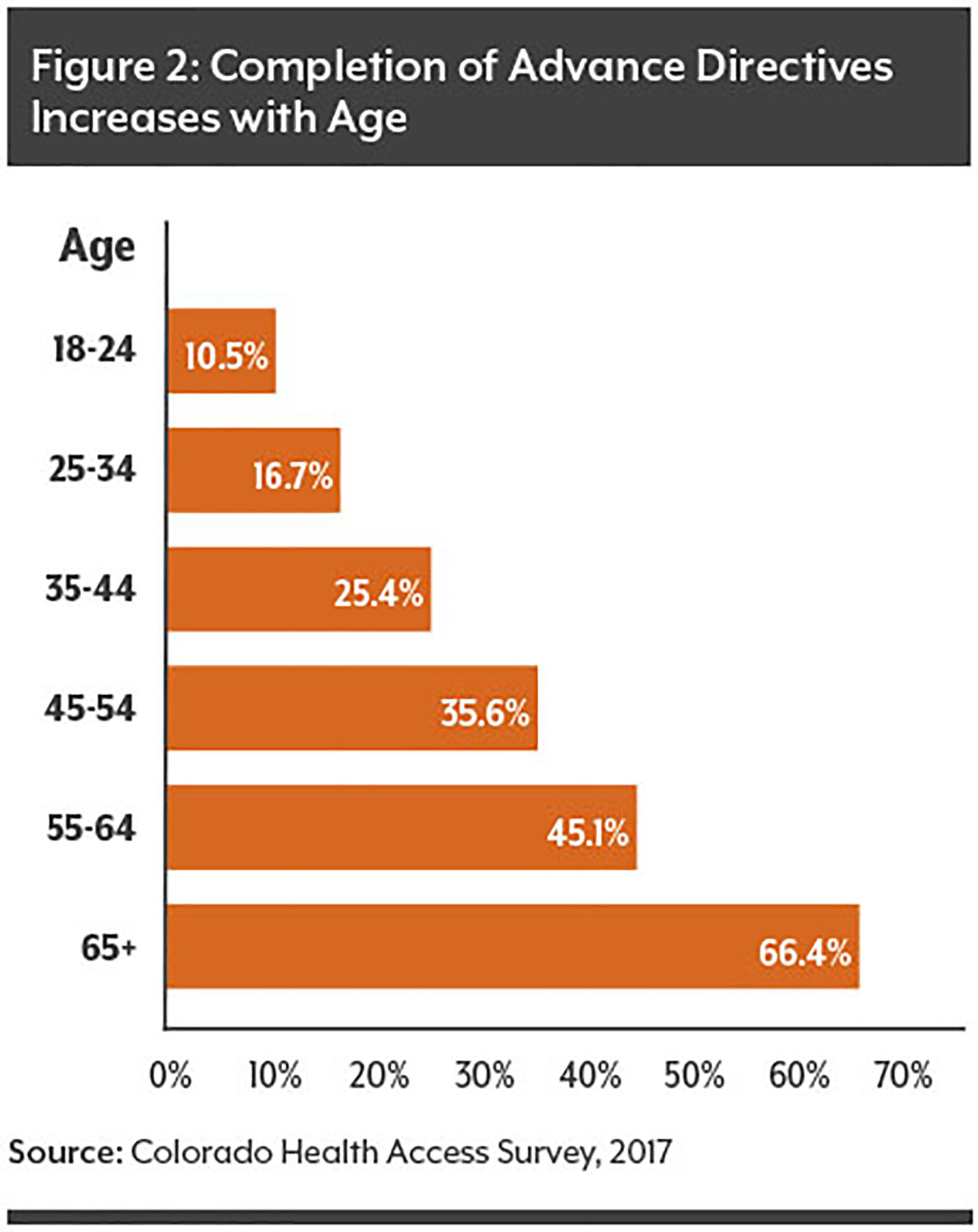

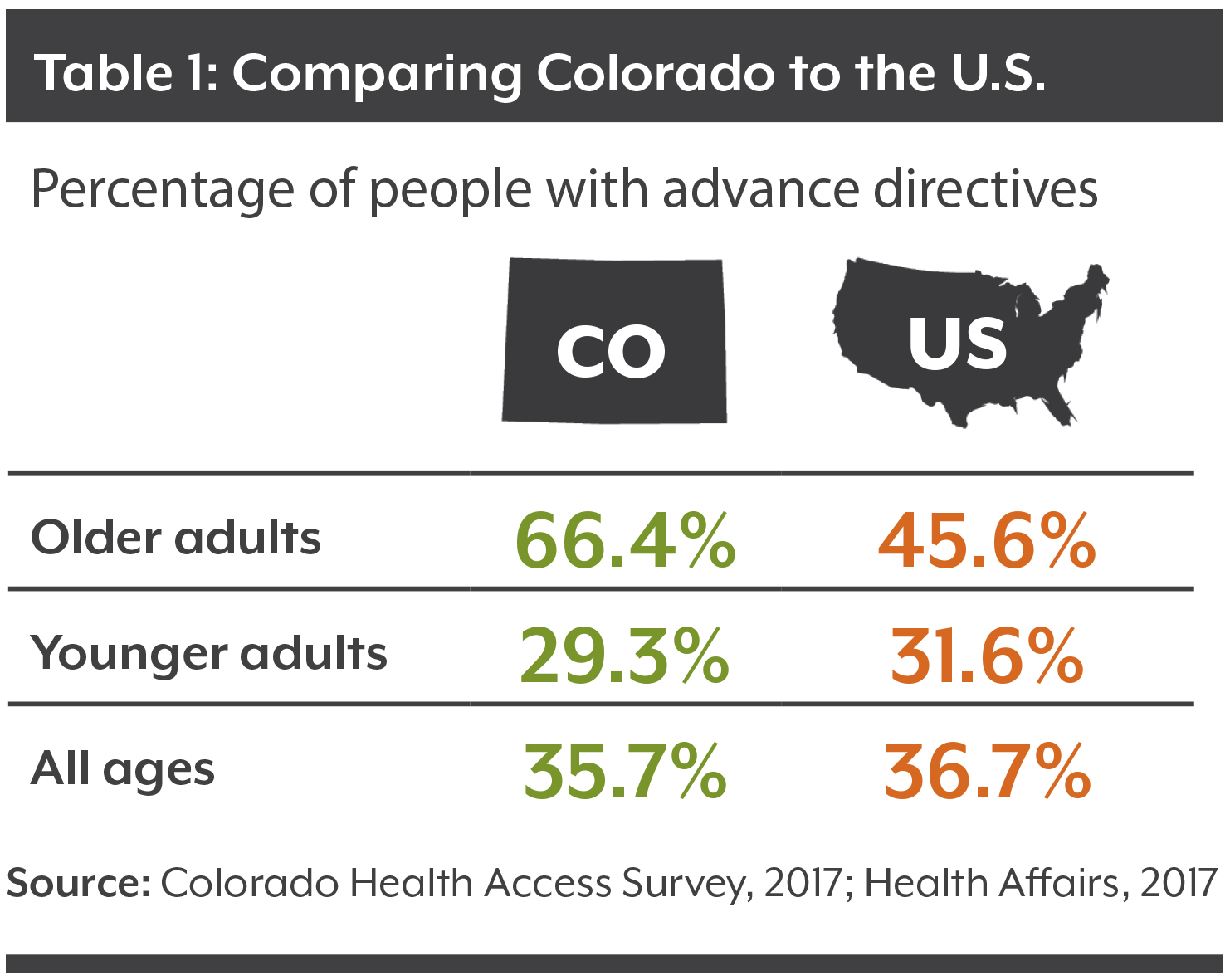

That’s one-third of all Coloradans aged 65 or older. Among younger residents, even fewer have completed advance directives.

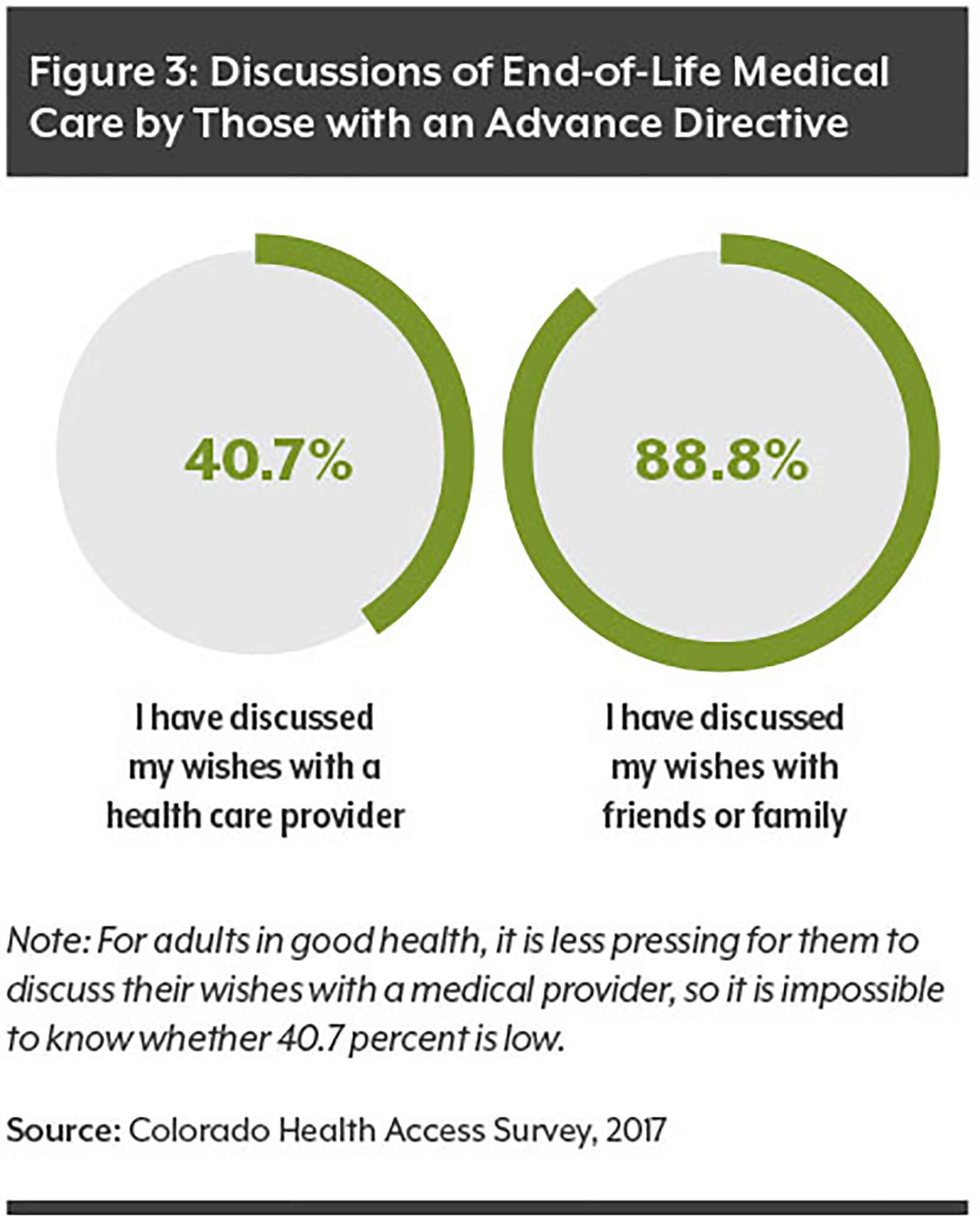

It’s tough for most people to think about — let alone talk about — dying. But those who make mindful efforts to communicate end-of-life preferences can increase their chances of receiving the type of medical care they want.

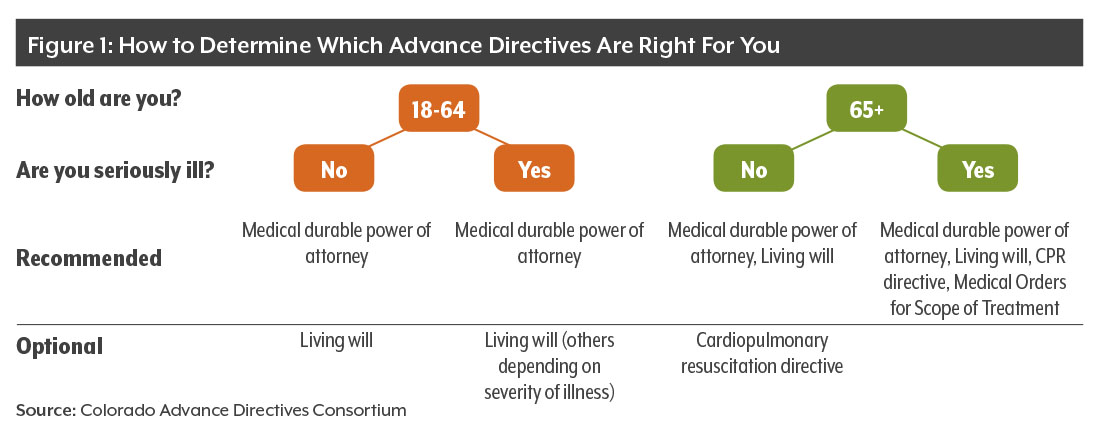

Advance directives can convey people’s wishes in writing when they are unable — cognitively or physically — to make decisions about their health care.

The 2017 Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS) included questions about advance directives for the first time in the survey’s history.

The topic is gaining increased attention for a number of reasons. Colorado’s population is aging rapidly. The state’s 65-plus age group is expected to increase 51 percent by 2030, from 812,600 to 1,226,300.

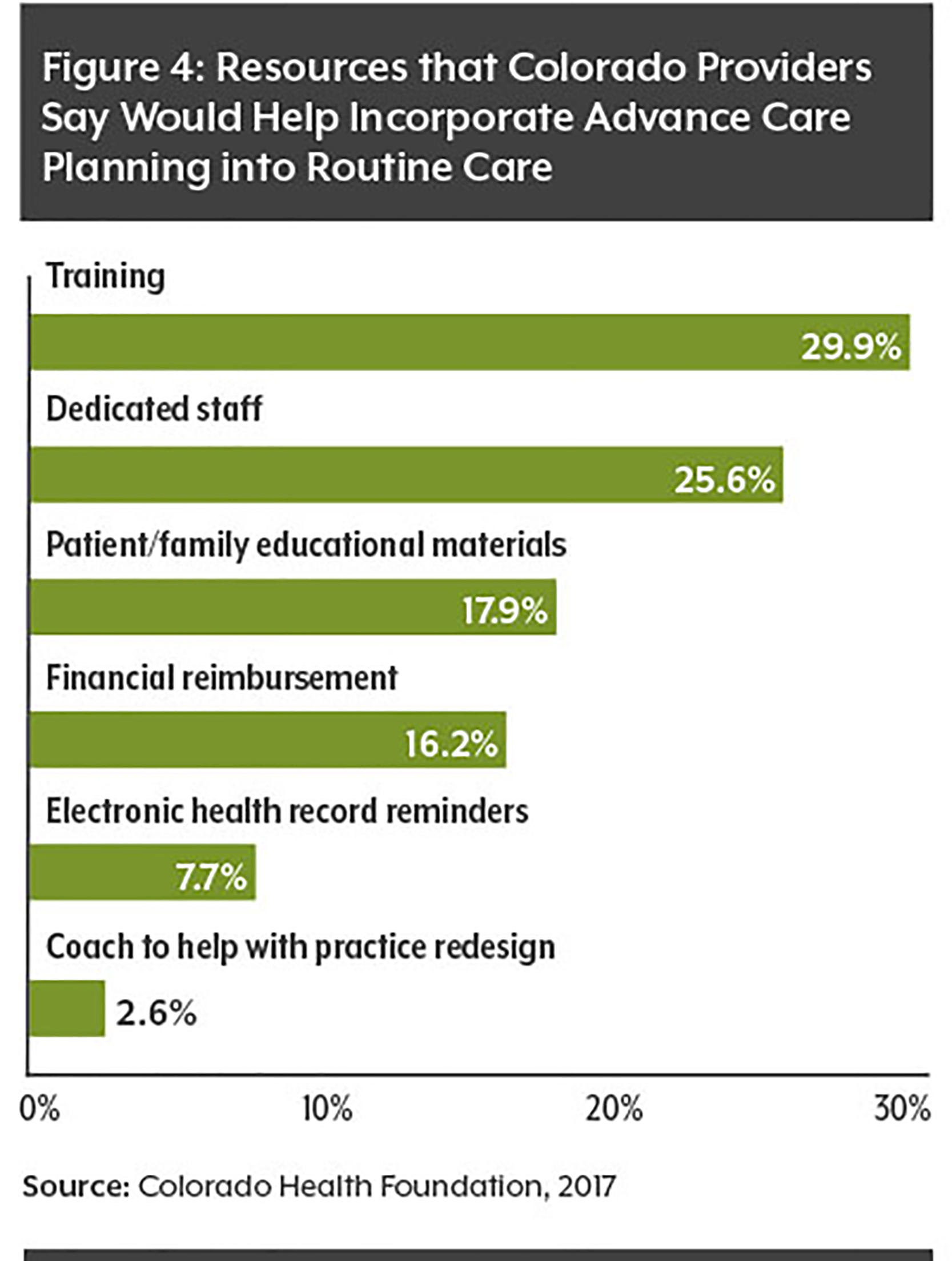

Meanwhile, advance care planning is associated with fewer hospitalizations, a lower likelihood of dying in the hospital, and increased use of hospice care.

Advance care planning also has the potential to reduce health care spending between five percent and 68 percent, according to a 2016 review of multiple studies.

All advance directives are optional, and they can be changed, updated or discarded at any point. Advance directives cost nothing, although if someone opts to use an attorney there would be a charge.

This paper analyzes the new CHAS data regarding advance directives, including their use by age, race/ethnicity and health status. It also examines efforts in Colorado to increase the use of advance directives.