The New Better

We are dealing with a lot. It’s common to hear people say they can’t wait for 2020 to end so we can go “back to normal.”

But the calendar did not cause these events. 2020 only brought the bitter harvest of seeds sown long ago. If we aim to return to normal, or even a “new normal,” we will find ourselves living through 2020 over and over again.

“We’ve learned a lot about ourselves during this pandemic,” said the Rev. Dr. Timothy Tyler, pastor of Shorter Community African Methodist Episcopal Church in Denver. “We’re going to have to be truthful about a system that has left so many people vulnerable for death and for sickness.”

Rather than a new normal, we need a New Better. We need ethical leadership to guide our city and state in a recovery that addresses long-neglected needs for equity and fairness in crucial parts of our public life — mental health, work, health care, education, housing.

To that end, the Colorado Health Institute (CHI) and The Denver Foundation present this report, which grew out of a series of conversations the two organizations held this summer with Colorado leaders. In dialogue with politicians, academicians, clergy, philanthropists, and clinicians, we identified areas we can shape in our emergence from the pandemic. Though not an exhaustive list, these three areas repeatedly surfaced as pressing and urgent with the leaders who spoke with us. They can be viewed as an introduction to how we, as a community, approach a New Better.

• Mental Health. The social isolation and anxiety brought about by physical distancing made clear that mental health is important to everyone. We won’t be able to promote good mental health by “medicalizing” the task, because we don’t have nearly enough therapists and psychiatrists — and especially lack people of color in the mental health profession. This is work for the community.

• Children, Families, and Schools. The pandemic revealed how much we count on our schools for more than education. They provide child care for working parents, social services, friendship, food, and safe spaces — important parts of life that online school cannot replicate. How will we address the widening gap in learning and child development and the harm to women’s careers that we have seen during the months that schools’ doors have been shut?

• Housing. Take a heated real estate market and gentrifying neighborhoods, and mix in a pandemic and a deep recession. The result is an intensified housing crisis, with its most visible aspect being encampments in front of the state Capitol and around Denver. Where can people experiencing homelessness go to be safe during a public health crisis? And what about the slow-moving public health crisis of unstable housing?

A pervasive theme throughout these topics, in all of our interviews and in our data research, is the great harm done to human lives by inequality and systemic racism. Disparities in treatment and outcomes are seen in the data, in our societal responses, and in our outcomes. Whether we examine housing or hunger, medical care or education, 2020 has not treated Coloradans uniformly. We share evidence of this inequality throughout this paper. We also recognize that systemic racism is so pervasive that it is itself a serious issue facing Colorado.

This paper sets the stage for further discussion, using a framework for ethical decision-making adapted from by the Aspen Ethical Leadership Program and its co-director, Dr. Matthew Wynia. Each section of the report poses questions for community leaders based on the Aspen program’s Triple A framework: Awareness, Analysis, and Action.

We invite you into this discussion. At the end of each section, we pose questions for us as a state and community to grapple with — beginning with a hosted roundtable on mental health — as we strive to create A New Better.

Our Sources

This paper draws on interviews with leaders in the Denver community, research and data analysis by CHI, and prior CHI projects that examine the social factors that influence health, the state of early childhood education, strategic planning to improve behavioral health, and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the people of Colorado.

We gratefully acknowledge the following people who shared their time and thoughts with us.

• J.J. Ament,

CEO of Metro Denver Economic

Development Corporation

• Vincent Atchity,

CEO of Mental Health Colorado

• Kelly Brough,

CEO of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce

• Carl Clark,

CEO of Mental Health Center of Denver

• Ben Miller,

Chief Strategy Officer for Well Being Trust

• The Rev. Dr. Timothy Tyler,

Shorter Community AME Church

• The Rev. Louise Westfall,

Central Presbyterian Church

The ideas of these servant-leaders permeate this paper, and quotations or paraphrases from our interviews with them appear in the sections titled What Leaders Are Saying.

The Triple A Framework for Ethical Decision-Making

Awareness: Recognize when you are facing an ethical issue.

Values: List the core or shared/common values that may be in conflict in this situation. Pay attention to how people’s differing experiences could affect the values they bring to the discussion.

Gut reaction: Can you acknowledge your gut reaction to the issue and then set it aside to do the analysis? How has your life experience shaped implicit biases you might be carrying?

Analysis: Study the ethical issue to arrive at a decision about the right thing to do

Who cares: What other individuals and groups have an important stake in the decision? What values are at stake for each?

Relevant facts: What clinical, legal, economic, or other facts should inform your decision? What information outside of data and figures – such as stories and lived experience – should be considered, and what might the data not show?

Choices: Name the available options and decide which option represents the values-based position you should seek to enact.

Action: Develop and practice executing your plan for how to do what’s right.

Reasons and rationalizations: Build your action plan using the previously listed data and your considerations about what each impacted stakeholder (including yourself) is concerned about, motivated by, and has at risk.

Script and rehearse: Create a tangible action plan to enact your values, and then spend time testing it.

Prevention: What should you do now to help avoid similar dilemmas arising in future?

CHI is grateful to The Denver Foundation for supporting and guiding The New Better project.

Getting Real About Mental Health

What the Pandemic Revealed

Often when people talk about mental health, they’re really talking about mental illness — a frame that allows the subject to be dismissed as someone else’s problem. The pandemic has deminstrated that mental health is a central part of daily life for all of us, not a specialized corner of health care.

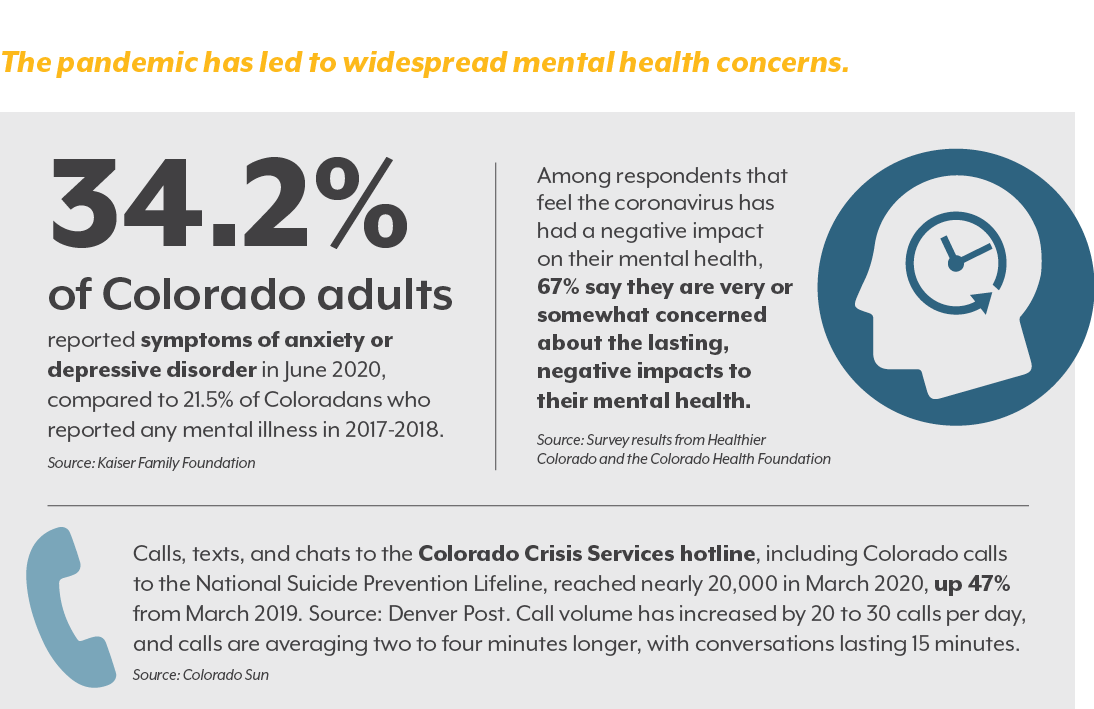

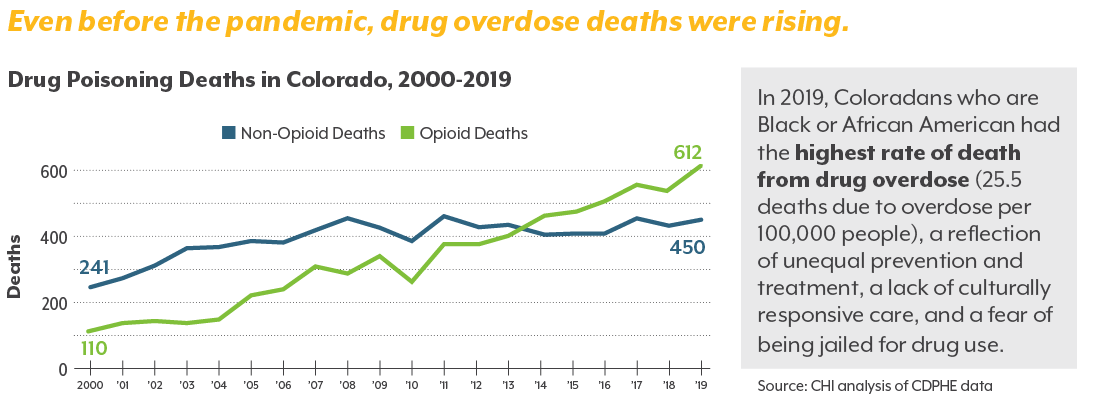

We’re dealing with a lot of loss — jobs, loved ones, familiar daily rhythms, faith in government and institutions. It’s no wonder that surveys and statistics show many people are struggling with mental health and are using more alcohol and drugs. The social isolation of the pandemic can be especially hard on people who have been marginalized, including immigrants, refugees, and people who identify as LGBTQ.

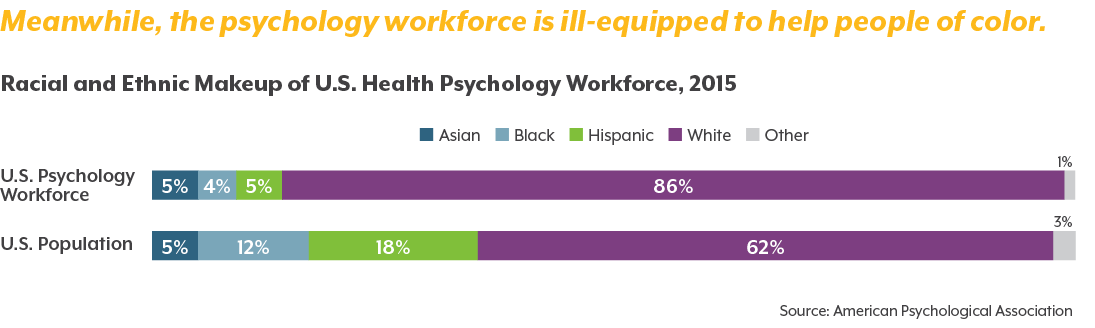

Coloradans had inadequate access to mental health care before the pandemic, and we don’t have a system in place to treat all these new needs in the old way. This is especially true for people of color. The Black Lives Matter movement has highlighted the generations-long legacy of racial discrimination and the toll that takes on mental health. Yet the psychology workforce is overwhelmingly white.

The New Better will be a transformation of our community into one where friends and neighbors feel comfortable talking about mental health and supporting each other, where people of color can address mental health on their own terms, and where policies and rules reflect the universal need for good mental health.

What Leaders Are Saying

• We are living through a triple pandemic, said Rev. Dr. Timothy Tyler of Shorter AME Church. People are experiencing an economic and racial pandemic stacked on top of COVID-19. “I think we’re going to head into a mental health crisis having to deal with the anxiety and the grief the pandemic has brought,” Tyler said. “Black Lives Matter and the pandemic all at once remind us that we have a weight on top of us as a people, and it seems like there’s no relief in sight.”

• The work of improving mental health must be owned by the community. It’s too big to be delegated solely to professional medical providers. For example, Vincent Atchity, CEO of Mental Health Colorado, said teachers sometimes tell him they’re not in the mental health business. “The mental health of children is very much the responsibility of people who are forming minds, and they need to own it,” he said.

• Mental health resources are sporadic and disconnected. There’s a profound need for integration, so that when a teacher, barber, or police officer encounters someone who needs help, they have an established path to follow, Atchity said.

• Stress is a real problem, and it is amplified during the pandemic. Carl Clark, CEO of Mental Health Center of Denver, hopes one of the lessons of the pandemic will be how to recognize and handle stress. “Stress is our body and mind telling us there’s something important to us that we’re worried about. As long as the stress is there, you’re having a physiological reaction, and you’re not doing anything,” Clark said.

• The mental health workforce needs to include more people of color. Generations of oppression have led to deep psychological effects, and patients often feel better talking with a counselor who shares a similar background, Clark said.

Challenges in Ethical Leadership

Awareness

What mental health issues have you become more aware of during the pandemic? Who is being affected the most?

Analysis

How can we address the increasing mental health needs both in medical and community settings, particularly the need for more people of color serving in the mental health professions and more culturally responsive approaches to mental health care?

Action

What is one thing any of us — employers, educators, policymakers, individuals — can do to promote good mental health throughout our community?

The Data

Children, Families, and Schools

What the Pandemic Revealed

Education is only part of the work of schools. They also provide food, human services, friendships, free child care for working parents, and the opportunity to connect with trusted adults. It was hard to fully appreciate these services, though, until they were gone.

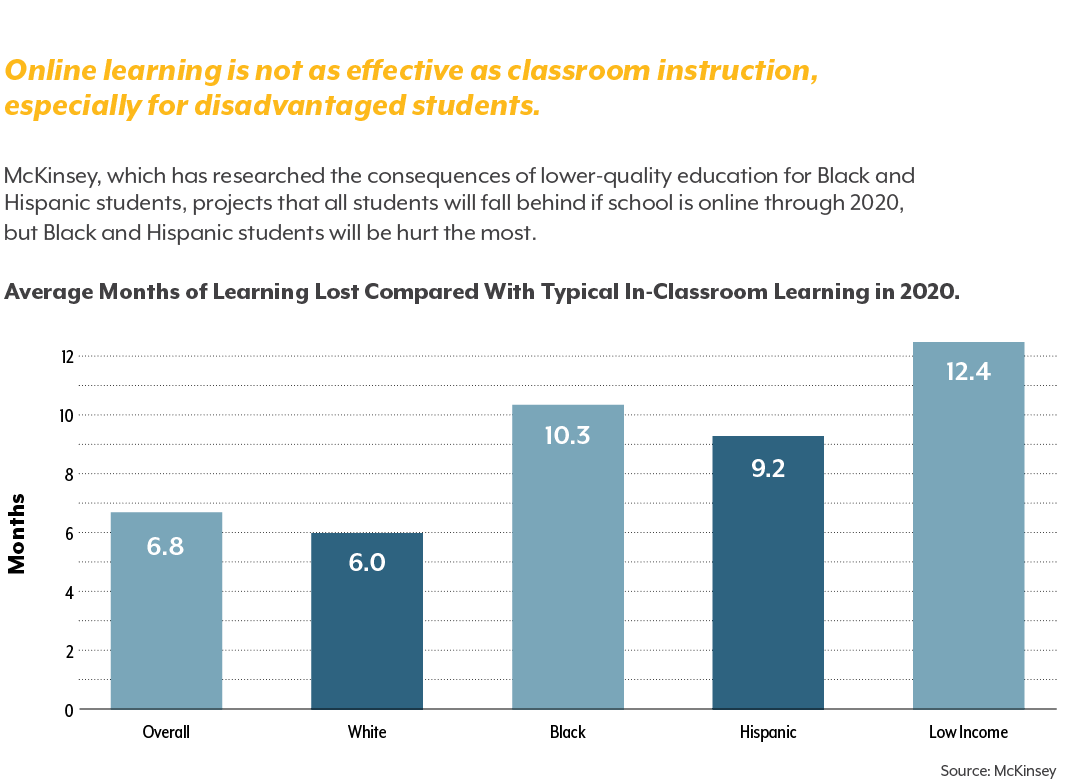

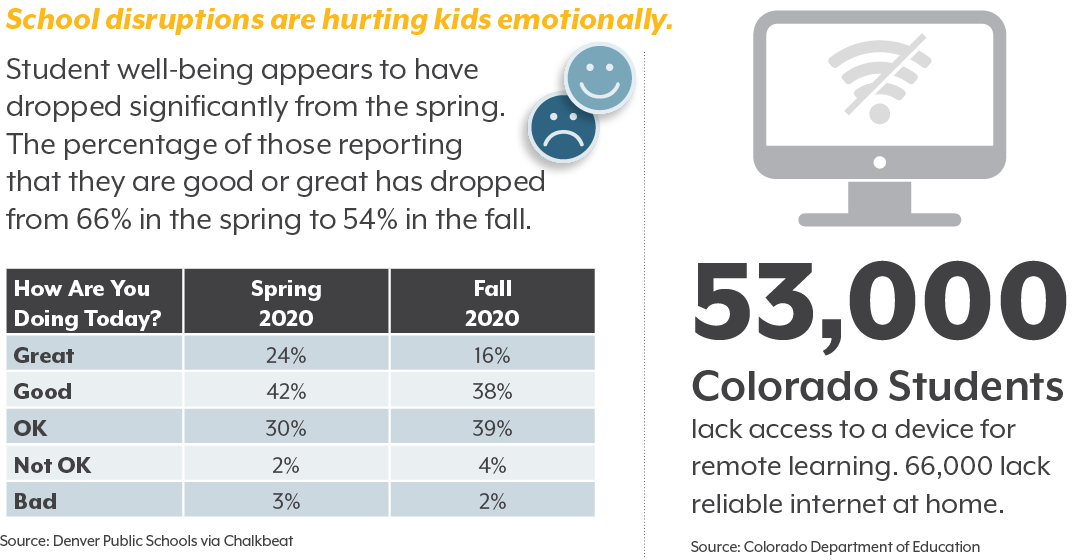

Some schools kept up their breakfast and lunch programs during the pandemic, but for the most part, online learning cannot supply all the other benefits for which families have come to depend on schools. Online school creates new barriers for many students, because they don’t have the home technology or the constant presence of a tech-savvy adult to keep students connected and on task. Some families have the money to hire tutors or create private learning pods. For those who do not, the education gap is likely to widen. The Associated Press and Chalkbeat found that districts with primarily white students are more than three times as likely to offer in-person school this fall than those that enroll primarily students of color.

Adams 12 Five-Star Schools recognized the inequity and addressed it by creating free learning pods to provide a safer, supervised learning experience for children whose parents cannot afford to hire private help.

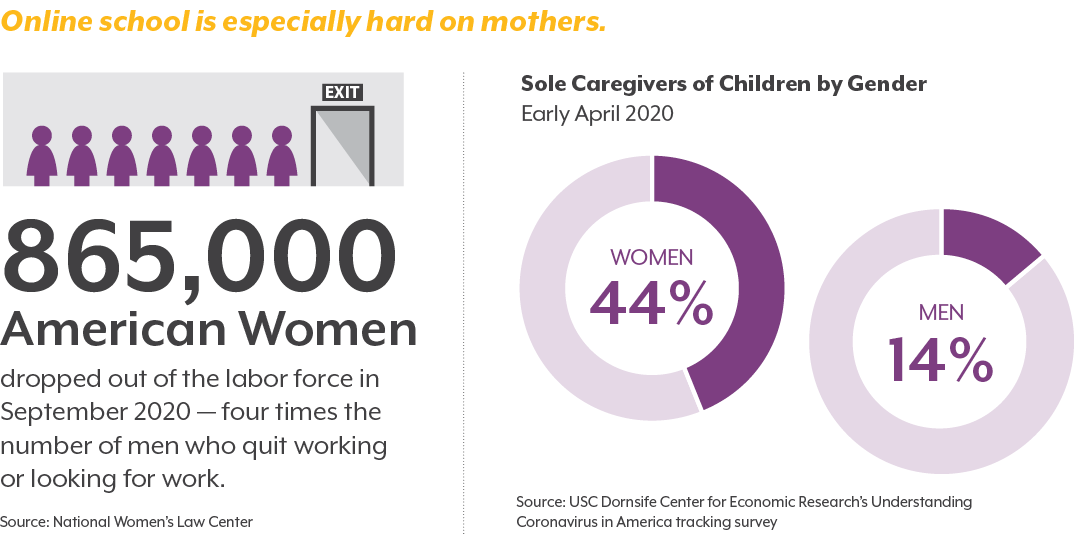

The loss of in-person school has been devastating for parents, especially mothers. New data show that alarming numbers women are leaving the workforce.

Innovative ideas like Adams 12’s learning pods are all too rare. What else can leaders do to improve school during and after the pandemic for all children and families, not just those with the most money and status?

What Leaders Are Saying

• Children are dealing with profound social and emotional anxieties, whether they are going to school online or in-person. Kids who can attend school worry about running out of Clorox wipes or getting their grandparents sick, said Ben Miller, Chief Strategy Officer for Well Being Trust, a foundation that works to advance mental, social, and spiritual health.

• Suicidal ideation among youth is spiking. Young people are willing to talk about mental health, but we haven’t provided a structure to give them someone to talk to. Often, kids with a mental health problem at school are more likely to receive a response from police than a counselor, Miller said.

• “We’re at major risk of having a generation that’s off a step with social-emotional development. It terrifies me.” Miller said. “I can’t imagine it’s not going to have a long-term impact.”

• Parents were already feeling the weight of worry about their children’s education before the pandemic, Tyler said. With online school, many parents have to go to work and cannot monitor their children all day to make sure they’re sitting at the computer. “I’m very concerned about the long-term lasting effects of what’s happening with the pandemic. I think we’re going to have to be intentional about connecting with our children.”

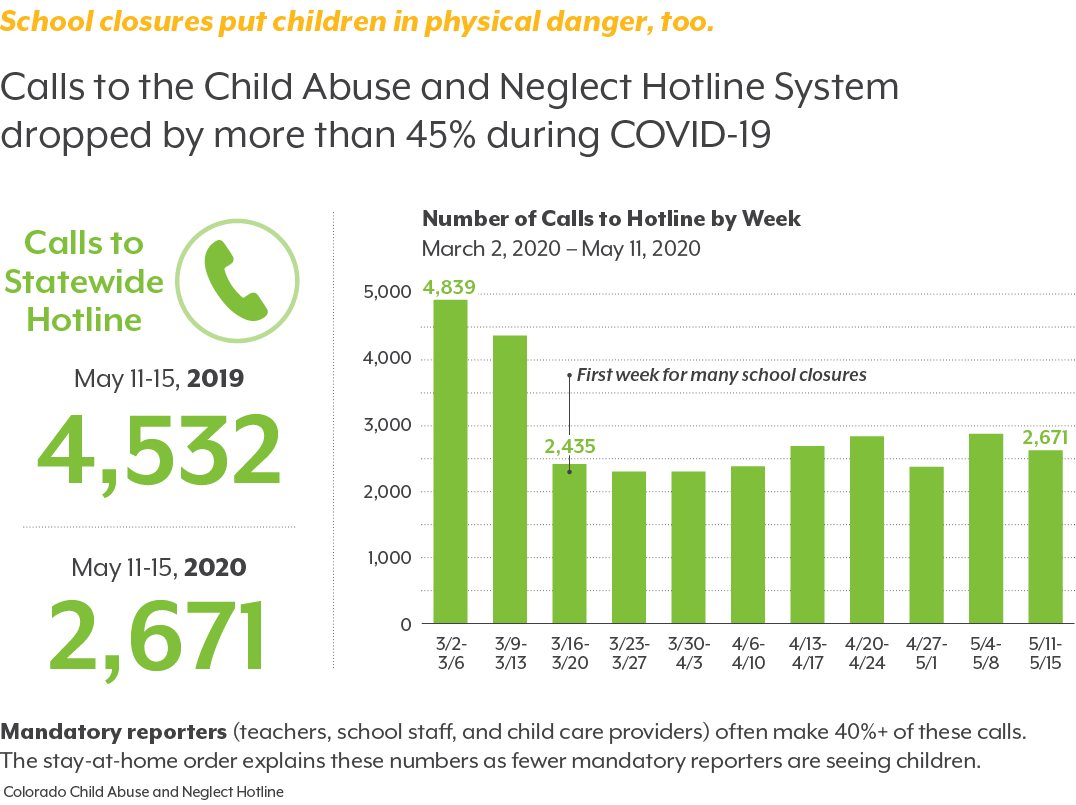

• Reports of domestic violence, child abuse, and death by suicide are all down during the pandemic, but the drop is likely due to a lack of reporting, Clark said. After other disasters, there has been a lag between the event and when deaths by suicide happen.

Challenges in Ethical Leadership

Awareness

How do we address the economic and emotional sacrifices of women and the mental (and sometimes physical) risks to children of prolonged isolation?

Analysis

How can we fairly account for all the benefits school provides — socialization, positive adult presences, child care, food, medical and social care? What is the value of that, and what is the consequence of losing it?

Action

What do we do about the academic progress that is lost during online schooling, especially among Black and Hispanic/Latinx students?

The Data

Housing and Homelessness

What the Pandemic Revealed

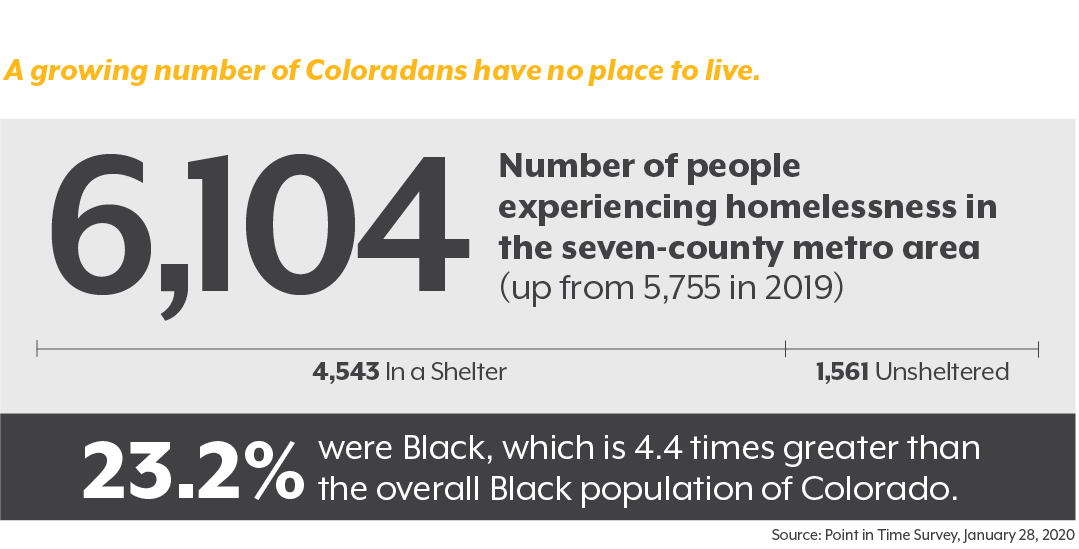

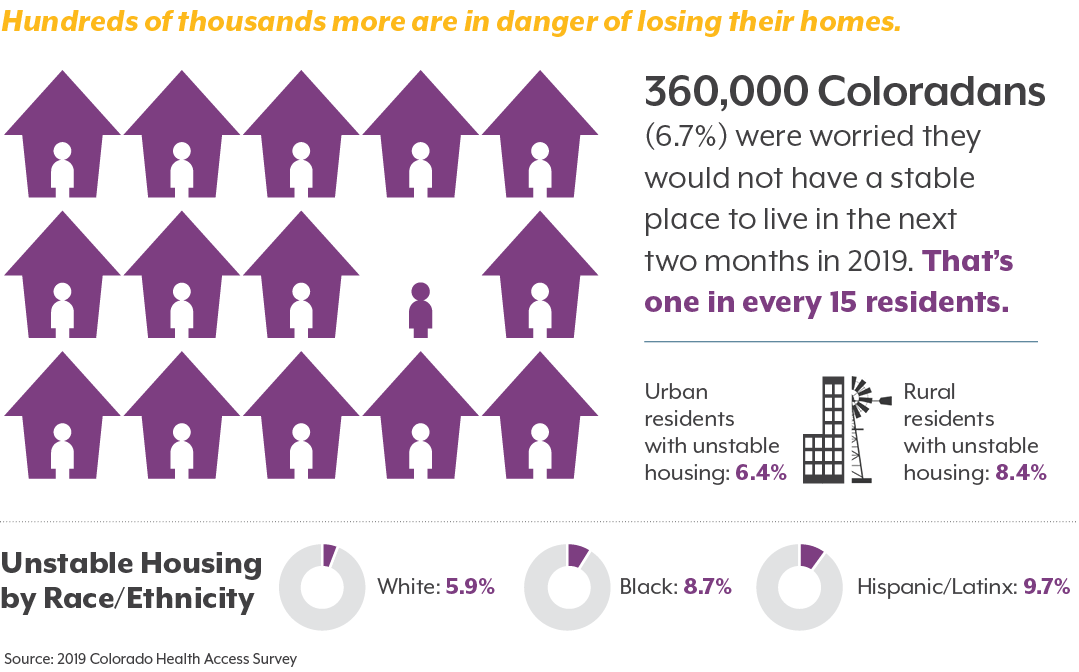

Housing and homelessness were growing problems before the pandemic and the recession it caused. In 2019, one in 15 Coloradans worried about having a place to live in the next two months. And a January 2020 count found more than 6,100 people experiencing homelessness in the Denver metro region — the highest number in at least six years of the survey. More than a decade ago, the city of Denver had a 10-year plan to end homelessness. And the city’s camping ban sparked years of controversy and legal challenges.

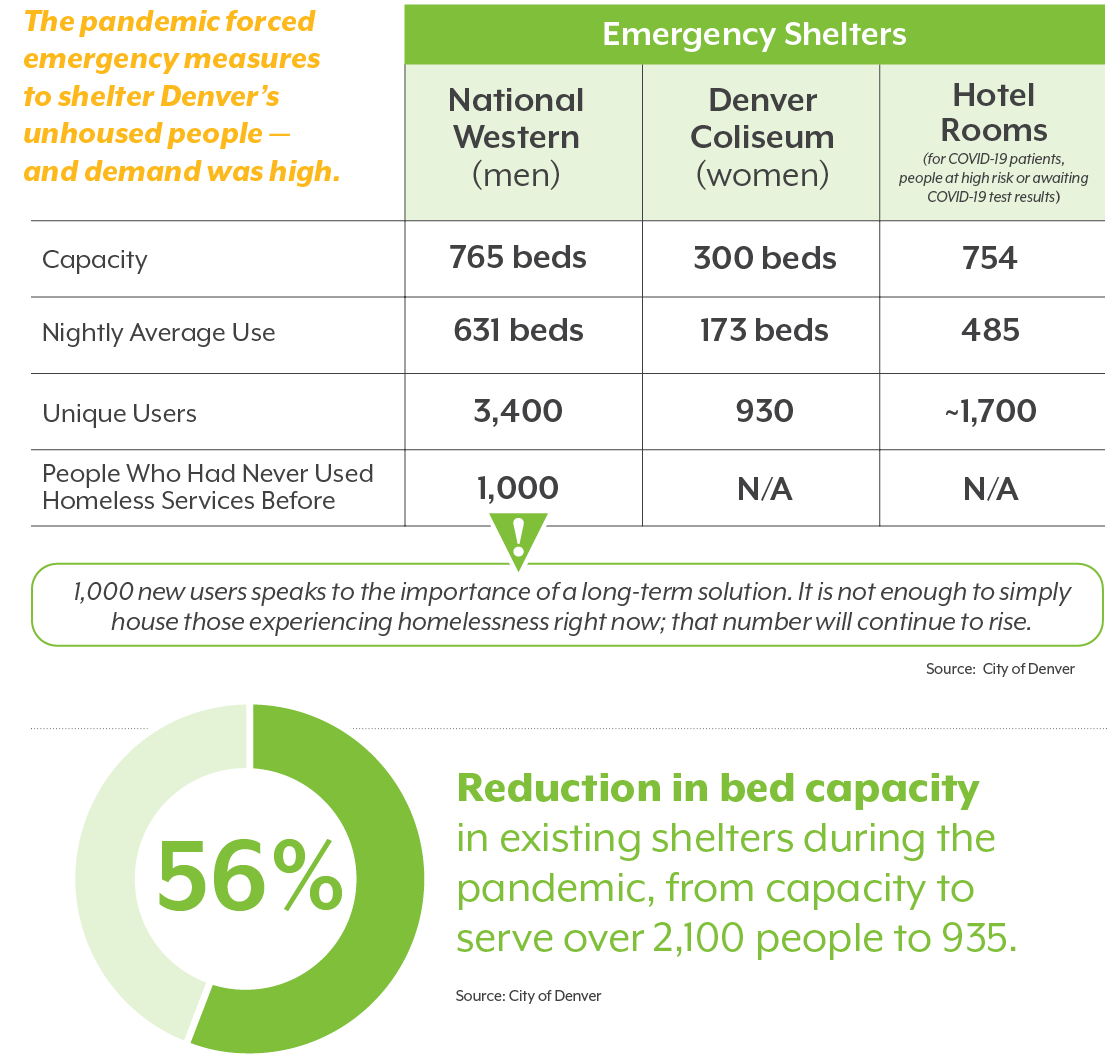

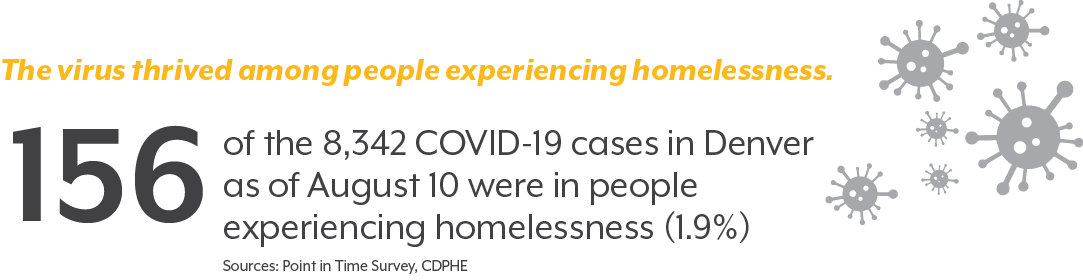

These issues came to a head when the governor issued a stay-at-home order in March 2020, followed by a Safer-at-Home policy that continues to this day. Thousands of Coloradans have no home to stay at and no “safer” place to escape the virus. Hundreds of thousands more have a home, but they don’t know for how long. The pandemic forced shelters to close, so the city scrambled to set up temporary shelters at the National Western Center and Denver Coliseum and secure hotel rooms for people most vulnerable to the virus.

The legacy of systemic racism is seen on the streets. Nearly a quarter of people experiencing homelessness in Denver are Black, far out of proportion to the overall Black population. The protests against police brutality and racism that began in May spotlighted the issue, as activists and people experiencing homelessness set up camps in highly visible spots, including the park outside the state Capitol.

The pandemic has heightened tensions that already existed over housing and homelessness. Solutions have eluded us for years, but now we need answers more than ever.

What Leaders Are Saying

Central Presbyterian Church runs a transitional housing program for men in the church building at 17th Avenue and Sherman Street. The Rev. Louise Westfall made several observations about how homelessness has changed during the pandemic:

• Day labor jobs have dried up, so more men are at the shelter during the day, which increases the risk for spreading the virus.

• Not only has the Denver metro area not addressed the issue of homelessness, but many people are getting angry about homelessness. It’s a psychology of victim blaming. The tent cities have become objects of scorn and derision.

• The city has put in portable toilets and showers, but that almost seems like an insult when the need is for large investments in supportive housing.

Challenges in Ethical Leadership

Awareness

What do a city and its people owe to the unhoused?

Analysis

What can we do to keep people in their homes during the recession and expand the availability of safe and affordable housing?

Action

How can cities create safe spaces for people experiencing homelessness — especially during a pandemic when shelters are closed?

The Data

“The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you can alter, even by a millimeter, the way people look at reality, then you can change the world.”

— James Baldwin

An Invitation

This paper is an invitation to the people of Colorado — an invitation to think and act with intentionality in framing questions, deeply considering options, and changing how we will live to provide hope for our future.

It is a tiny step — maybe just a millimeter — toward a New Better.