The May SNAC Lab featured a provocative talk about the possibilities and roadblocks to health system reform from someone who has deep experience in both public health and medical care — Dr. Bill Burman, director of Denver Public Health and former interim CEO of Denver Health and Hospital Authority.

Burman shared his frustrations at a national health system that spends too much on medical treatment and produces worse results than other countries. He also shared success stories and his sense of optimism that it is possible to reform the system to meet the Triple Aim of better care, better health and lower costs.

Takeaways

Burman made three main points in his presentation:

- It is possible for the U.S. health system to achieve the Triple Aim, but it won’t happen through the tinkering that has characterized health reform efforts to date.

- Universal coverage and a better payment model both would help achieve the goal.

- A broader view of health is needed, with more than lip service paid to prevention of health problems instead of paying for medical treatment once problems have already arisen.

The SNAC LAB Presentation

Over the years, SNAC Labs have focused on specific initiatives and reforms to Colorado’s health care safety net, from Medicaid’s Accountable Care Collaborative to expanded dental access to studies of emergency department users. The context for all these reforms is the Triple Aim — the idea that better health care for patient, better health outcomes for the population and lower health costs are all necessary to achieve simultaneously.

In May’s SNAC Lab, Burman took a step back from the usual focus on specific programs to offer a gut-check about the country’s overall progress toward health system reform. His talk was at once sobering and optimistic.

“Although the Triple Aim might seem impossible, I argue it is eminently possible, but we’re not going to get there by tinkering,” Burman said.

The system pays little more than lip service to prevention in general and to addiction in particular, he said.

“We need to take addiction seriously. We say we do, but we don’t,” Burman said.

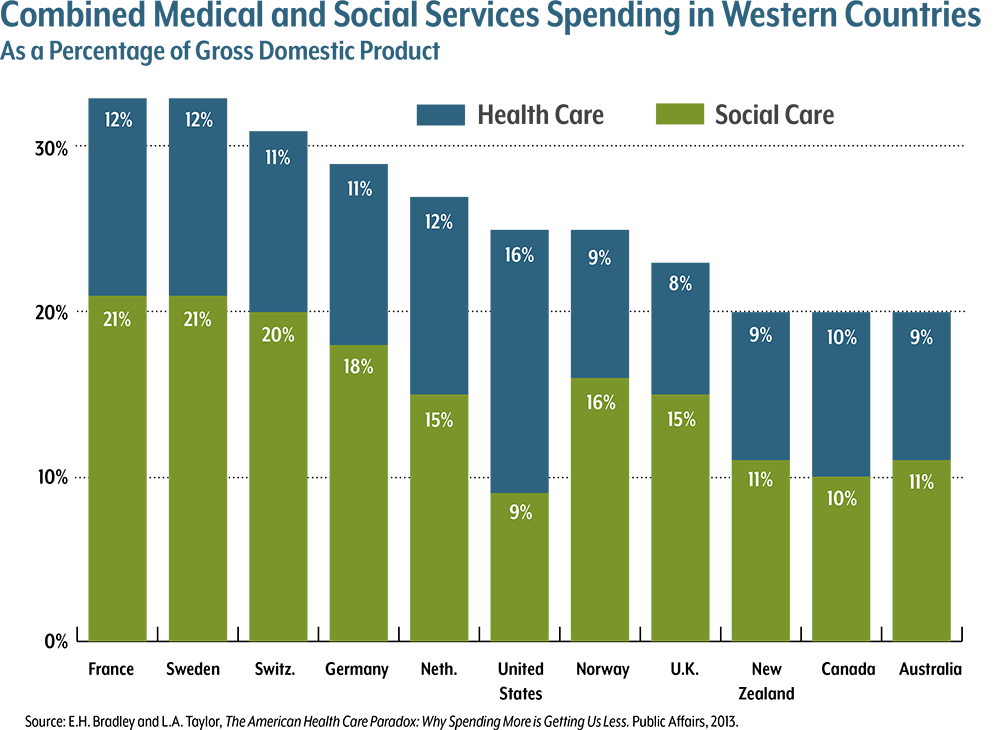

He showed a well-known graph of health care spending as a percentage of gross domestic product for the industrialized nations. The United States spends far more than other countries and achieves worse health outcomes.

“We are an utter failure,” Burman said. “If this were a business, we would be bankrupt long ago.”

But the graph also provides a reason for hope. The fact that other countries have healthier populations while spending less shows the Triple Aim is achievable, he said. It doesn’t require a United Kingdom-style national health system, either. Australia and Germany both have multiple providers and multiple payers, and they achieve similar high results and lower costs.