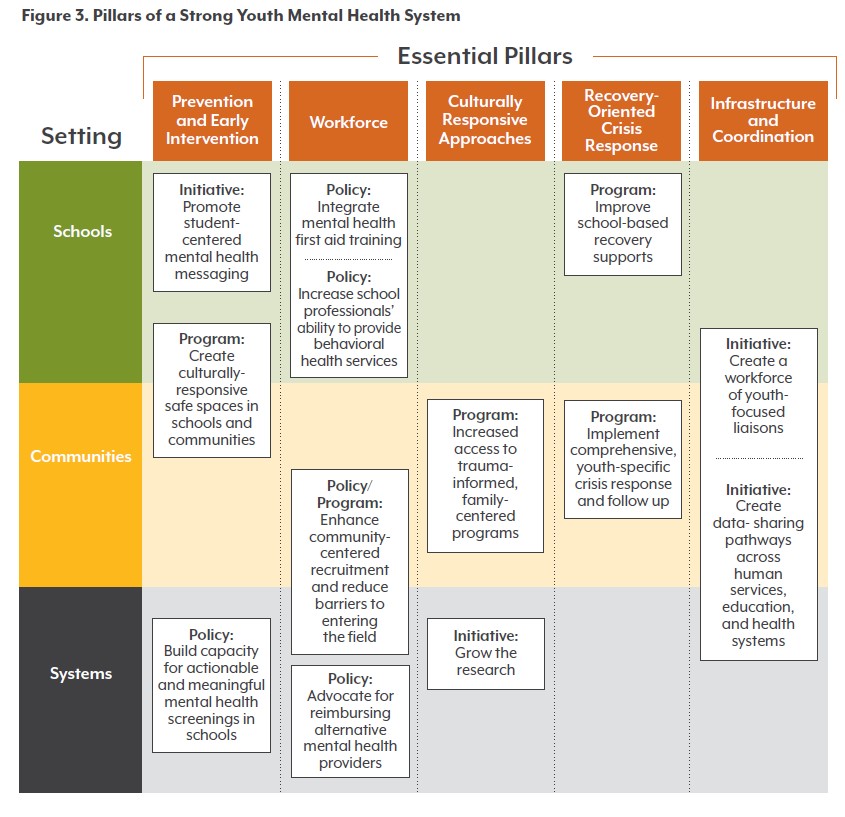

Pillar 2: Workforce

Importance and Key Findings

Workforce shortfalls disproportionately hurt youth and families who are people of color, immigrants, and who do not speak English as a first language. Families enrolled in Medicaid, who have lower incomes, or who lack insurance are more likely to access care from community mental health centers, which are short-staffed statewide.(8)

Youth participants in this project shared concerns about school counselors coming off as judgmental, while people from community-based organizations worried that providers would not be able to handle caseloads if screening is increased in schools.

With only one in five providers identifying as nonwhite, Colorado must recruit and retain behavioral health professionals who can provide culturally sensitive and responsive care.(9) Timely access to culturally competent providers is also needed to improve quality of care and adequate continuity of care and follow-up. Access to culturally responsive providers helps families avoid being retraumatized by the system and ensures that programs and services are delivered and conveyed in ways that make sense and are meaningful to youth and families.

Identified Solutions

The behavioral health workforce serving youth is insufficient in capacity and diversity. School leaders should integrate mental health first aid training for all educational staff. Community leaders and policymakers must enhance opportunities for community-centered recruitment.

Schools

Policy: Integrate mental health first aid training. Every school staff member, and other professionals involved in the school ecosystem, must become part of Colorado’s youth mental health workforce. School leaders should integrate mental health first aid as part of all school and supporting staff’s yearly trainings across all middle and high schools. This should include all in-school staff as well as support and service professionals such as bus drivers. Youth mental health first aid training has been shown to increase teachers’ knowledge and ability to address the mental health needs of their students, alongside an increased understanding of their own mental health.(10)

Key Criteria: Evidence-Informed | Sustainable | Timely

Spotlight:

Legislation such as Senate Bill (SB) 20-001 in Colorado would have expanded behavioral health training for K-12 educators. However, it failed, likely due to COVID-related time limitations during the shortened 2020 legislative session and lack of funds during that year.

Expanded training along the lines of what Pioneer Ridge Elementary School in Johnstown has done to train teachers and other school staff can help support addressing mental health emergencies.

Future research needed: Investigate how to best carve out time for educators to be trained and identify ways to make trainings more interactive, applicable to real-life scenarios, and culturally responsive.

Policy: Increase school mental health professionals’ ability to provide behavioral health services. Build capacity for schools to support school counselors, social workers, and psychologists in recognizing and responding to specific mental health disorders, generational trauma, and other needs with a youth-focused lens — rather than primarily as disciplinarians, college counselors, or homeroom teachers.

Key Criteria: Equitable | Sustainable | Timely

Spotlight: The Oklahoma Comprehensive School Counseling Framework recommends school counselors devote 80% of their time providing services to students and encourages them to deliver mental health month activities, promote mental health awareness, and teach cultural competency to students. The framework also positions school counselors as vital members of the student crisis response team.

Future research needed: Consider what legislative changes or processes are needed to support schools in transforming how they use their behavioral health staff.

Communities/Systems

Program: Enhance community-centered recruitment and reduce barriers to entering the field. Philanthropic and state leaders should support community-based organizations and providers, in the form of grants or stipends, to recruit and retain a culturally and linguistically competent behavioral health workforce. Community-based efforts should include creating early career exploration programs, job shadows, and internships for youth as early as middle school. Funders can also look at providing scholarships or stipends for people in entry-level positions, such as certified nursing assistants, medical assistants, or paraprofessionals, to reduce administrative and financial burdens and support those entering advanced degree programs in mental health. Stipends for multicultural and multilingual providers can also support diversification of the workforce.

Key Criteria: Equitable | Sustainable | Timely

Spotlight: The Center for African American Health’s Workforce Readiness Program supports youth ages 14-24 with work experience and skills, including opportunities to explore careers in health care and health-related areas, to increase care and advocacy that is representative of the community.

As part of its 2020-23 unified state plan, Hawaii’s adult and youth workforce development services reach Native Hawaiians through intentional outreach at their own community events, rather than events held by the workforce development agency. These services include guidance with individual assessments and employment plans, and financial assistance for tuition and books, leading to employment that includes careers in mental health.

New Mexico’s Expanding Opportunities Project provides reimbursements, stipends (up to $300 for licensing), and loan repayments for students obtaining a degree that leads to licensure as a school-based behavioral health provider. Students must commit to working in the state and serve at a “high-need” school for at least 24 months after graduation.

SB 5092 in Washington appropriated $250,000 to develop “a language access plan that addresses equity and access for immigrant, multilingual providers, caregivers, and families across the educational sector.” This includes a scan of best practices relevant to multilingual workforce development. Recommendations include “funding new or expanded programs that provide support for multicultural or multilingual beginning educators.”

Future research needed: Engage and align with efforts led by workforce development centers; the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment’s Office of the Future of Work, including Apprenticeship Colorado; the Behavioral Health Administration; and other leaders considering workforce development initiatives. This includes determining equitable reimbursement from payers. Further investigate and address the common barriers — financial and otherwise — that multicultural and multilingual students face when pursuing mental health careers.

Policy: Advocate for alternative mental health workers to be billable by Medicaid. Community health workers such as promotoras, trusted community gatekeepers, and peer support specialists are the most attuned to the needs of their own communities. This group can improve health by facilitating coordination of mental health care, enhancing access to community-based services around mental health, and informing solutions to address the social determinants of health needs in the community.

Key Criteria: Equitable | Evidence-Informed | Sustainable | Timely

Spotlight: Currently, 22 states reimburse community health workers through their Medicaid programs.(11) SB 58 in New Mexico allowed for certification of community health workers through the state’s Medicaid system and implemented protocols to get them certified. If adopted, Colorado’s SB23-002 would authorize Colorado to seek federal authorization to reimburse community health workers through Medicaid.

Future research needed: Engage with communities to identify and scale up culturally and linguistically responsive alternative mental health workforces, such as peer supports. For example, the Youth Era program in Oregon provides one-on-one, drop-in peer support programing. It trains Youth Peer Support Specialists who have lived experience in youth-serving systems, such as mental health, foster care, and juvenile justice, to support youth and young adults ages 14 to 25.