Colorado is often celebrated as a fit and healthy state, but when it comes to behavioral health, there’s more cause for concern than celebration.

Colorado ranks 43rd in the country for mental health, according to a 2018 index created by Mental Health America. It has the ninth highest rate of suicide in the country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports. And it is the only state where residents are heavy consumers of four different substances: alcohol, marijuana, opioids, and cocaine.

It’s clear that behavioral health is a challenge in Colorado. Yet many residents of the Centennial State do not get access to the treatment they need, according to the Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS), a biennial survey of 10,000 Colorado residents.

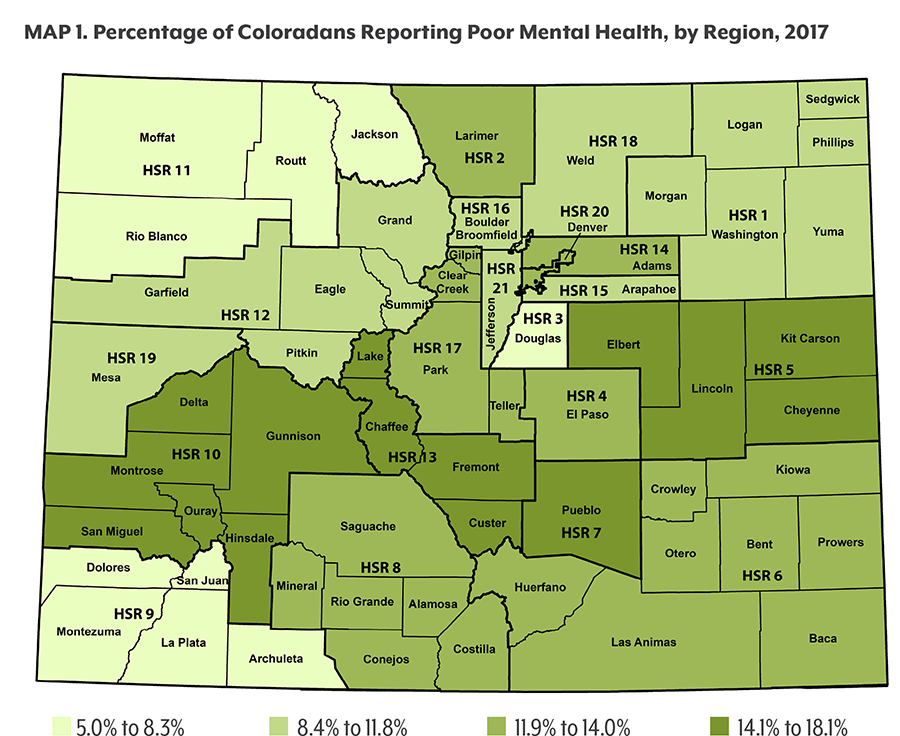

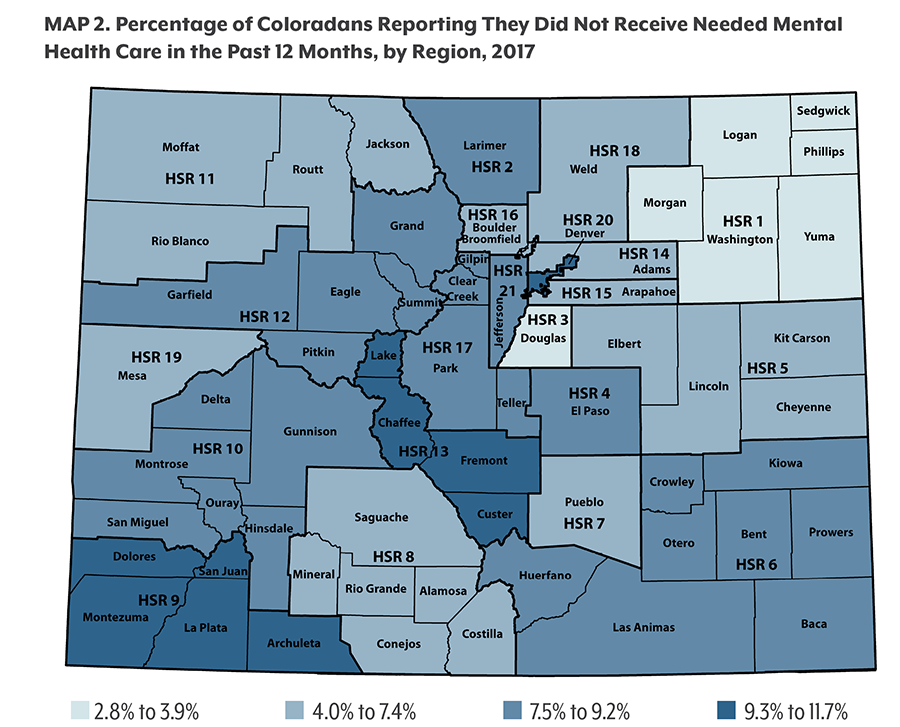

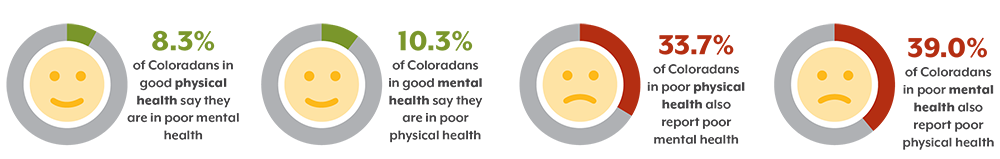

Nearly one of eight Coloradans report experiencing poor mental health in the past month, according to the 2017 survey. One of 13 said they did not get the mental health services they needed.

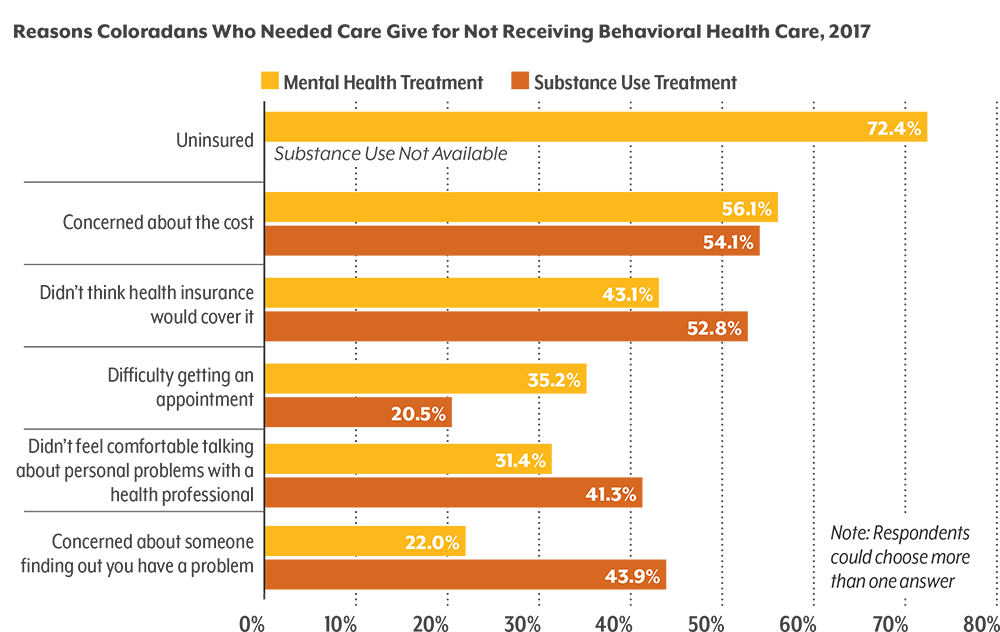

People with lower incomes are struggling the most. In 2017, these Coloradans reported both the highest rates of poor mental health and the least access to the care they need. Cost, stigma, and difficulty making appointments are all persistent barriers to treatment for mental health and for substance use.

But there is some good news. More people said they were able to access mental health care in 2017 than in 2015, and fewer said they didn’t get care because of the stigma around mental illness. And since 2013, significantly fewer Coloradans say they did not get needed care because it cost too much.

This report provides a closer look at which Coloradans report poor mental health and trouble accessing care. It also examines the barriers that prevent people from getting the care they need.

The project described was supported by Funding Opportunity Number CMS-1G1-14-001 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The Colorado State Innovation Model (SIM), a four-year initiative, is funded by up to $65 million from CMS. The content provided is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of HHS or any of its agencies.

The project described was supported by Funding Opportunity Number CMS-1G1-14-001 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The Colorado State Innovation Model (SIM), a four-year initiative, is funded by up to $65 million from CMS. The content provided is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of HHS or any of its agencies.