The Power of a Percent: CBO, AHCA and the Art of Estimation

Today, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published new estimates of the American Health Care Act’s impact. The ACHA is expected to save $119 billion over a decade but leave 23 million more Americans uninsured by 2026.

These findings have huge implications for the future of the GOP plan. The score means the Senate may now take up the bill under its rules for budget reconciliation, which requires only a simple majority vote to pass and is not subject to a Democratic filibuster. The latest CBO report projects less budget savings and a slightly lower uninsured rate than the previous CBO report in March, which predicted 24 million people would be uninsured. The increase of insured people would happen because more Americans would be expected to buy cheaper insurance plans, which have higher out-of-pocket costs, according to the CBO.

Given the importance of these scores, you may be wondering how CBO analysts predict the future. Truth is, they can’t — as CHI has discussed before, no one can. The CBO employs some of the country’s best economic minds, but they’d be the first to admit that today’s estimates are just that: estimates.

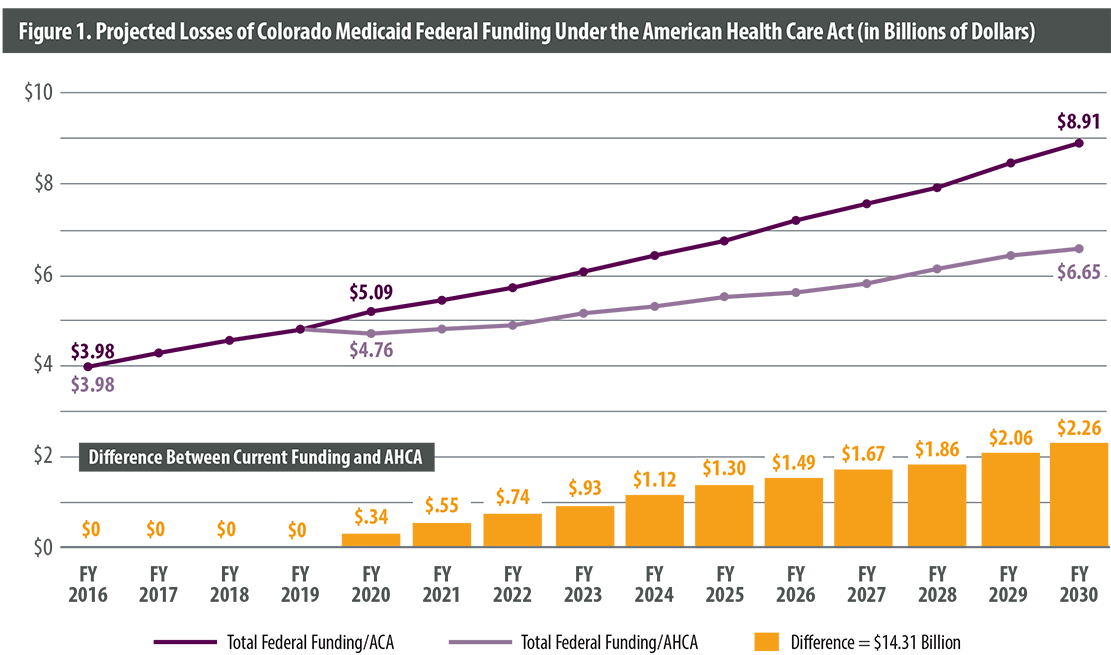

Economic impact models must make assumptions about an uncertain future. Take, for example, Colorado’s Medicaid program, which CHI recently projected would lose $14 billion in federal support over the first decade of the AHCA.

Our analysis assumes that medical care inflation, which the AHCA would use to grow federal support for state programs, will be the same in the future as it was from 2007 to 2016.

But what if we’re wrong? What if medical care inflation between 2020 and 2030 is higher than it was in the past? What if it slows?

This isn’t an impossible scenario. While we used a 10-year average to estimate inflation, year-over-year changes from 2007 to 2016 ranged from 2.0 percent to 4.1 percent.

If we’re wrong about medical care inflation by even one percentage point, the state’s losses would range anywhere from $8 billion to $20 billion.

But the potential for such drastically different outcomes doesn’t mean there are no lessons here. In fact, uncertainty itself may be the most important takeaway.

Medicaid spending is already unpredictable. No one knows when a flu outbreak will raise treatment costs or a recession will push enrollment higher.

Today, the federal government is committed to helping states pay for sudden increases in spending. This commitment makes federal spending less predictable but gives states some degree of security and certainty.

By switching from an open-ended obligation to a per capita cap, the federal government can better plan how much it will spend on the program every year. Unexpected expenses would fall to the state alone.

Whatever number you use to predict medical care inflation, this shift lies at the heart of the AHCA’s changes to Medicaid. It means more certainty for the federal government and greater risk for states.

That’s a trade-off that attracts some lawmakers and makes others nervous. The debate will continue as the AHCA moves to the Senate.