Changing the “Public Charge” and Health Insurance in Colorado

Key Takeaways

A new CHI analysis estimates 75,000 Coloradans would lose health insurance under a proposed Trump administration rule.

While the rule ostensibly focuses on immigrants, three-quarters of those who would likely lose insurance are U.S. citizens.

Nearly two-thirds of those who would lose coverage are children. The change would more than double the uninsured rate among Colorado’s kids.

Introduction

The latest Trump administration proposal with big implications for health insurance coverage has a surprising origin: the Department of Homeland Security.

It comes in the form of a change to the “public charge” criteria.1 Among other things, the new rule would allow the government to consider use of public health coverage — Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) — when deciding whether to allow an immigrant entry into the U.S. or issue a green card.

The proposal was published on the Department of Homeland Security website on September 22. Unlike previous drafts, this proposal does not allow immigration decisions to be based on the use of these benefits by an immigrant’s dependents. But confusion over the details of the 447-page proposal will likely lead to a “chilling effect,” or disenrollment of immigrants’ children even though they are not subject to the new requirements.

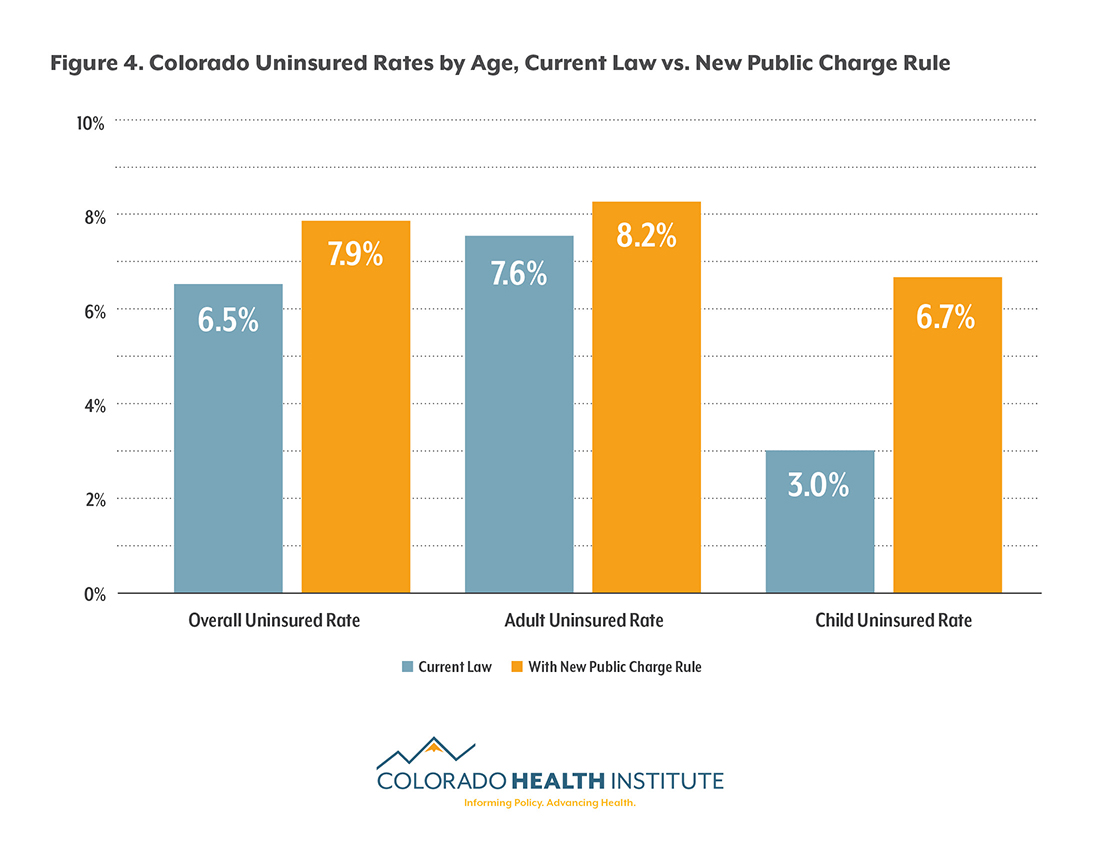

A new analysis by the nonpartisan Colorado Health Institute (CHI) estimates that 75,000 Coloradans would lose health coverage if the proposal takes effect, raising the state’s uninsured rate from 6.5 percent to 7.9 percent.

This means the public charge rule could be among the largest changes to insurance coverage from the Trump administration so far.

Public Charge in Immigration Law

“Public charge” may sound like an antiquated phrase, and in fact, it is literally older than sliced bread.2 The term first appeared in the Immigration Act of 1882.3 The idea was that the U.S. could prohibit the entry of some prospective immigrants, including those who could not demonstrate their ability to financially support themselves without becoming a “public charge.” The exact interpretation of who qualifies as a public charge has varied over the years.

In 1999, the government provided formal guidance on the public charge concept.4 Federal immigration officials said an immigrant’s likelihood of using public cash assistance programs should be weighed when determining whether to grant entry to the U.S. or allow a person already here to obtain a permanent resident card, commonly known as a green card.

In September 2018, the Trump administration proposed a change to this guidance. The proposed rule would allow immigration officials to now consider the use of a broader range of public benefit programs — including Medicaid (Colorado's Medicaid program is known as Health First Colorado) and CHIP (called the Child Health Plan Plus or CHP+ in Colorado).5

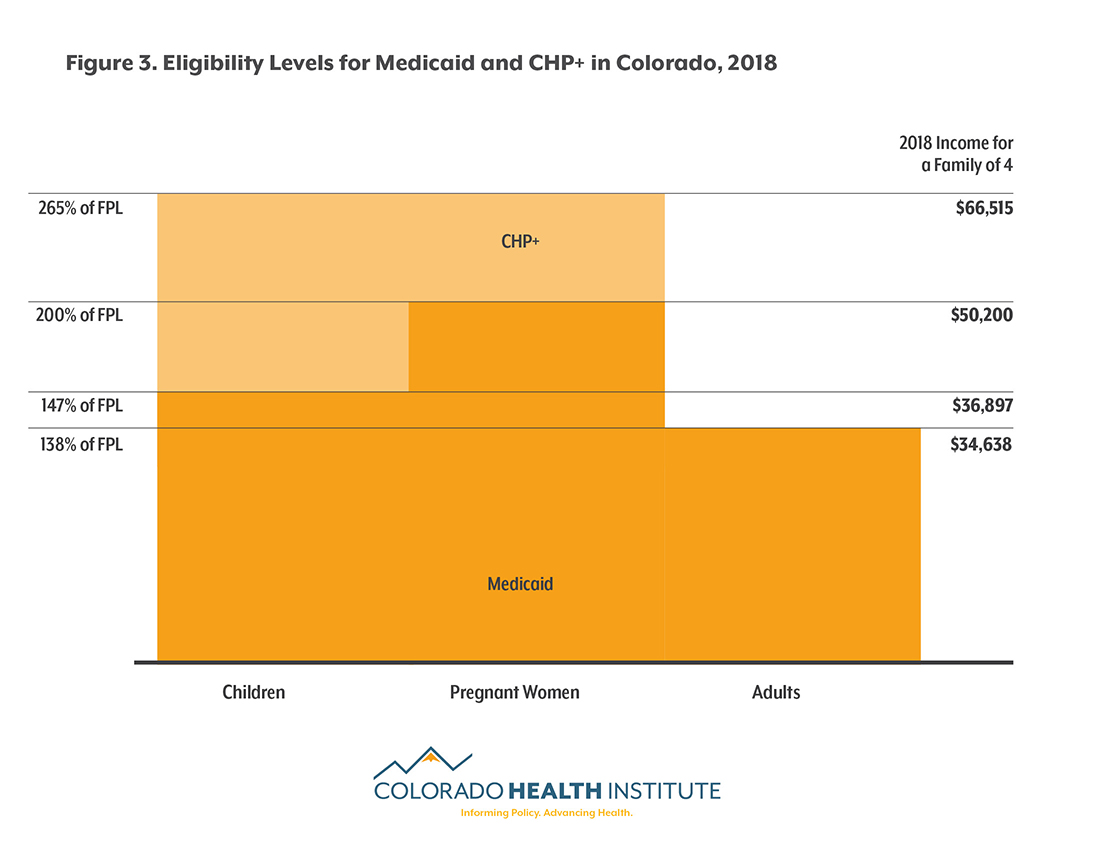

The proposed rules explicitly include Medicaid in the list of programs to be considered. They don't include CHIP, but do seek comment on whether or not the program, which provides coverage for some pregnant women and children (see Figure 3), should be included. CHI included CHP+ enrollment in its analysis in order to evaluate the impact of the new rules if the program is included and to account for any changes in enrollment that might result from confusion or concern about the rule.

Not every immigrant would be subject to this rule. Refugees and asylees would be exempt, as would immigrants who are already citizens or green card holders. Undocumented immigrants would not be affected, as they are already disqualified from enrolling in Medicaid or CHP+. (See Figure 1).

Individual Policies, Family Decisions

Officially, very few of Colorado’s Medicaid and CHP+ enrollees would be subject to the rule.

That’s because, with few exceptions, lawfully present non-citizens can only use public health insurance once they have been in the U.S. for five years or longer. The public charge regulation would only affect visa and green card applicants. Therefore, it would only come into play when a lawfully present immigrant has lived in the U.S. for five years but still does not have legal permanent residency.

That’s the rule’s official focus. But decades of evidence show that, in practice, the impact will likely be larger.

Many decisions about the use of public benefits are made at the family level. Qualification for these programs is generally based on household, not individual, income. Families eat meals, and therefore use food stamps, together. More often than not, all members of a family have the same health insurance.6

It’s therefore very difficult for a policy change targeting the use of public benefits by one household member to avoid having spillover effects on others.

For example, in 2014 Colorado expanded its Medicaid program to cover more adults. But enrollment among children grew as well — despite no change to their eligibility.7 This phenomenon, called the “welcome mat” effect, is an example of how a policy overtly targeting one family member can affect others.

Conversely, when immigration criteria for food stamp qualification changed in 1996, use of the program declined not only among those who were subject to the change. Enrollment among immigrant households with at least one citizen child dropped by 31 percent, even though these children’s eligibility for food stamps did not change.8

It’s not just confusion about new rules that can dampen the use of public benefits. A recent report by the Denver-based Mile High Health Alliance, a health-focused nonprofit, found that nearly nine in 10 Denver-area safety net providers reported a drop in the use of health care by immigrants and refugees concurrent with increased anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric at the federal level.9

This analysis quantifies the likely impacts of the new rule. CHI estimated the “chilling effect” of benefit use would be similar to the reduction in benefits by children in the aforementioned food stamp example (31 percent).

Coverage Impacts

More than 75,000 Coloradans who use Medicaid and CHP+ would become uninsured in 2019 under the new proposal, according to CHI’s analysis.10 Nearly three-quarters of those projected to lose their coverage are U.S. citizens, and nearly two-thirds are children (see Figure 2).

Coloradans who lose coverage will face challenges finding a new source of health insurance. By definition, families who qualify for these programs have lower incomes (see Figure 3). And with the rising costs of health insurance, it can prove very difficult to find affordable insurance on the individual market.11

The rule could have a significant impact on the state’s historically low uninsured rate. According to the Colorado Health Access Survey, 6.5 percent of Coloradans were uninsured in 2017. An additional 75,000 uninsured people would increase the rate to 7.9 percent. Most of the change would be driven by children, whose uninsured rate would more than double (see Figure 4).

Financial Impacts

The public charge rule could also affect Colorado’s budget and economy.

First, a drop in public health coverage could mean savings to the state budget. CHI estimates that state expenditures on Medicaid and CHP+ could decline by three percent ($107 million) in 2019 if 75,000 people were no longer insured through these programs.

However, new costs to the state may arise at the same time. For example, declines in insurance rates often mean increased emergency room use, much of which is covered by public funds in the form of emergency Medicaid or federal support to hospitals for uncompensated care. States with lower spending on government health care benefits often find themselves spending more money in areas such as school-based health care or corrections as a result. 12, 13

And the state budget is not the only financial arena where changes will occur. Loss of health insurance coverage can have larger economic impacts as well, such as lower work productivity or decreased spending on goods when families have less financial security.

Conclusion

As of September 2018, no changes have been officially made to the public charge rule. The use of health insurance programs by an immigrant cannot currently be considered in a green card application or when weighing decisions about entry into the U.S.

But experience with previous changes to the public charge rule shows the proposed change is likely to have effects far beyond the group that would be subject to the rule. CHI’s analysis suggests that the proposed changes could lead to more than 75,000 Colorado residents, most of them U.S. citizen children, losing their health insurance — a result that would have a broad effect on individuals and on the state’s health care system and economy.

Sources

[1] Department of Homeland Security. (2018). Inadmissability on Public Charge Grounds. Unofficial proposed rule. Available at: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/18_0921_USCIS_Proposed-Rule-Public-Charge.pdf

[2] Sliced bread hit the market in 1928.

[3] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2012). “Overview of INS History: USCIS History Office and Library.” https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/History%20and%20Genealogy/Our%20History/INS%20History/INSHistory.pdf

[4] Federal Register Publications. (1999). “Field Guidance on Deportability and Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds.” https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/FR/HTML/FR/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-54070/0-0-0-54088/0-0-0-55744.html

[5] Other programs that could be considered part of “public charge” assessments in the proposal include food stamps and housing benefits.

[6] Colorado Health Institute. (2017). Colorado Health Access Survey.

[7] Colorado Health Institute. (2016). Medicaid Expansion in Colorado: An Analysis of Enrollment, Costs and Benefits—and How They Exceeded Expectations. Available at: https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/medicaid-expansion-colorado

[8] Fix, M. and Passel, JS. (1999). Trends in Noncitizens’ and Citizens’ Use of Public Benefits Following Welfare Reform: 1994-1997. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/trends-noncitizens-and-citizens-use-public-benefits-following-welfare-reform

[9] Navas, D. et al. (2018). “Decline in access to healthcare through safety-net clinics by immigrants and refugees in Denver.” Mile High Health Alliance. Available at: http://milehighhealthalliance.org/key-documents-reports/immigrant-health-drop-off-report-final-3-18/

[10] Please visit the following link for a detailed methodology: https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/methodology-changing-public-charge-and-health-insurance-colorado

[11] Colorado Health Institute. (2018). “2019 Insurance Prices Bring Stability At Last.” https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/2019-insurance-prices-bring-stability-last

[12] The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. (2015). “The Effects of the Medicaid Expansion on State Budgets: An Early Look in Select States.” Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. Available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-the-effects-of-the-medicaid-expansion-on-state-budgets-an-early-look-in-select-states

[13] Dorn, S. et al. (2014). “What Is the Result of States Not Expanding Medicaid?” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22816/413192-What-is-the-Result-of-States-Not-Expanding-Medicaid-.PDF

Cover image: "Lawful Permanent Resident" by Max Braun, licensed under CC 2.0

Update: This piece was updated to clarify that public comment is not open as of October 5 2018.

This piece was updated to clarify that the rules do not explicitly include CHIP / CHP+, but do seek comment on whether it should be included. CHI's analysis included CHP+ in order to evaluate the impact of the new rules if the program is included and to account for any chilling effect on CHP+ enrollment that might result from the new rules.