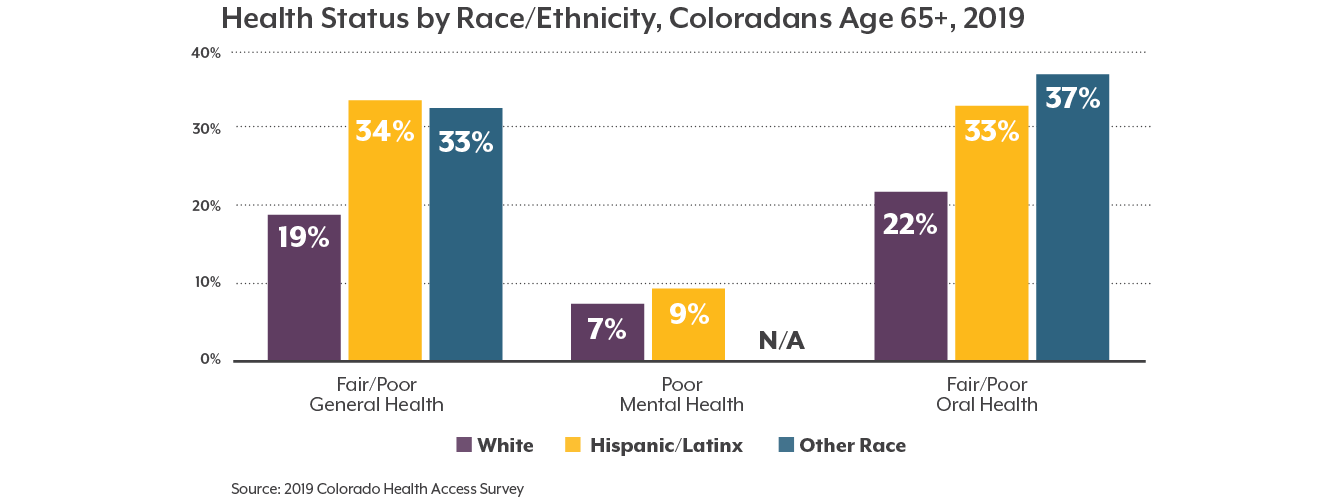

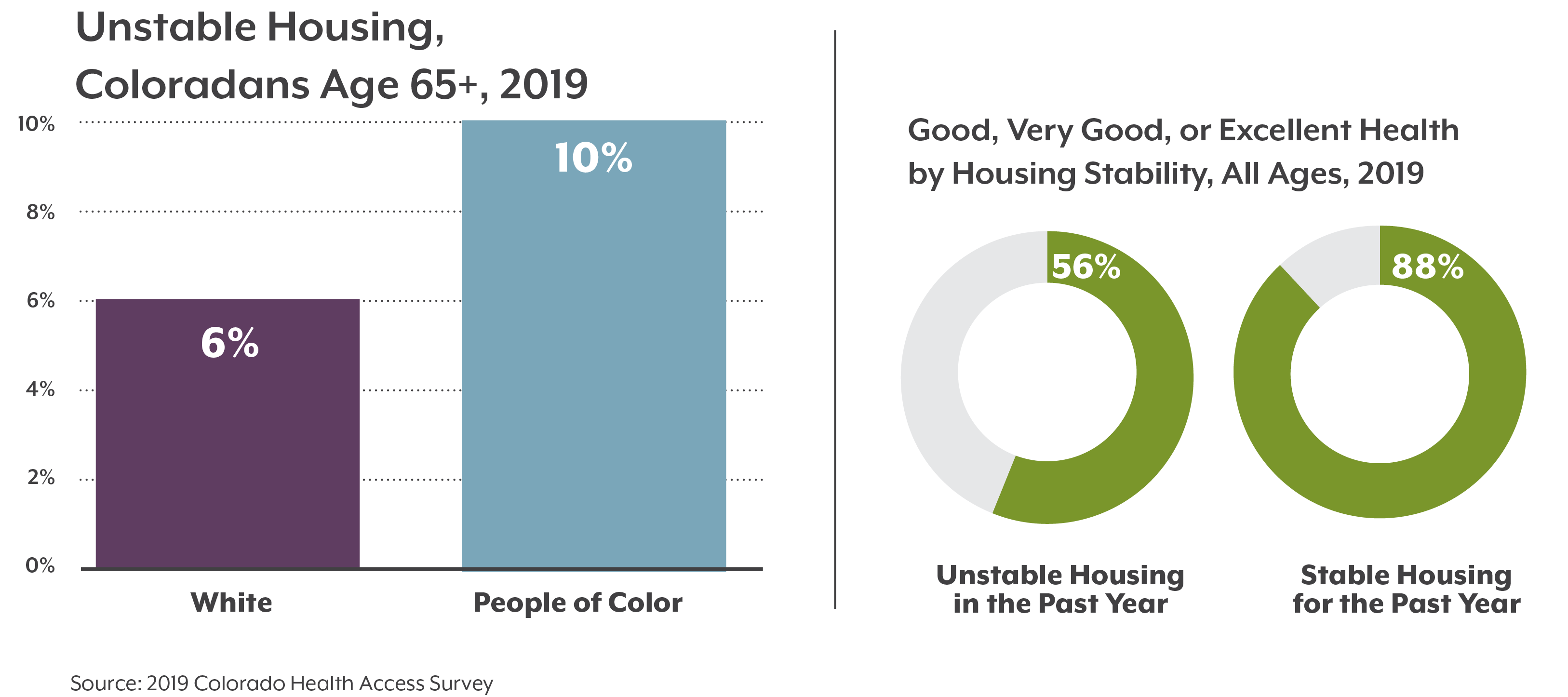

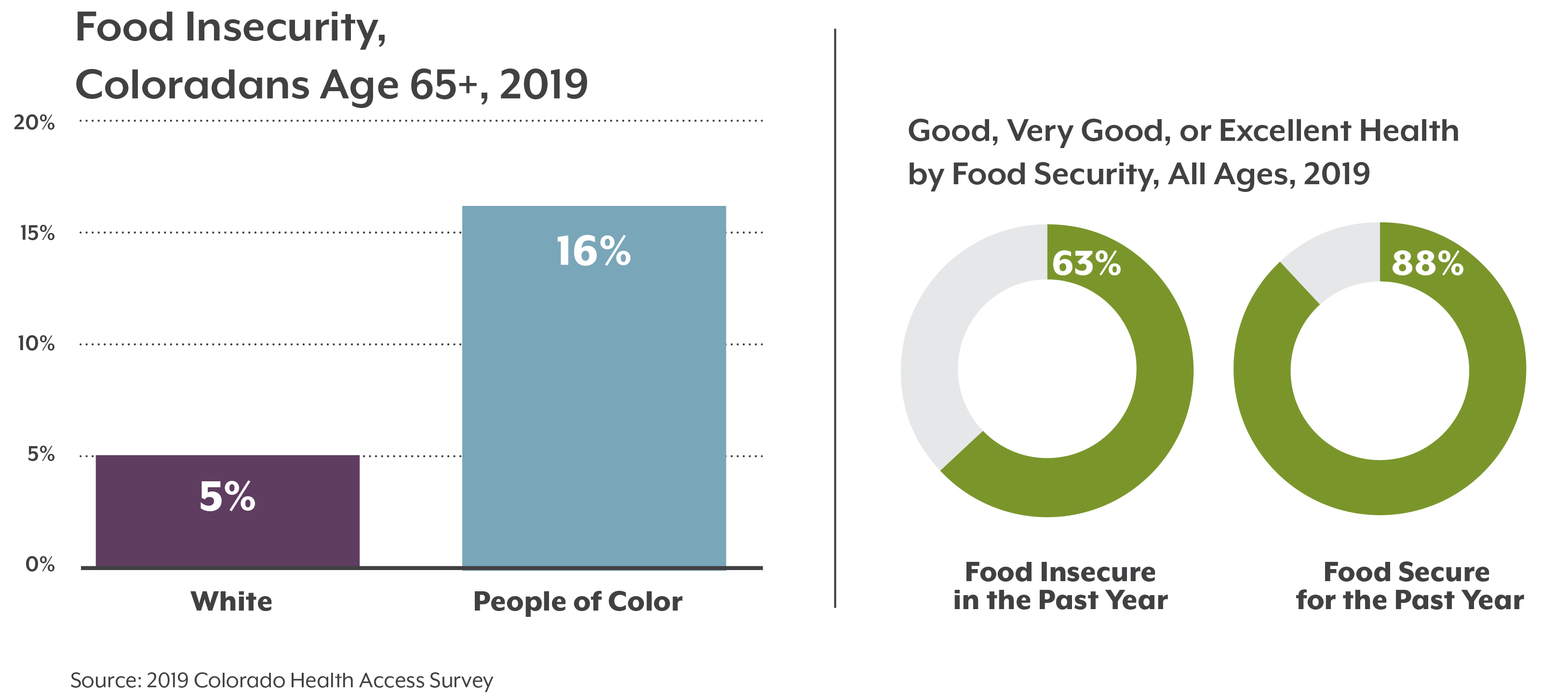

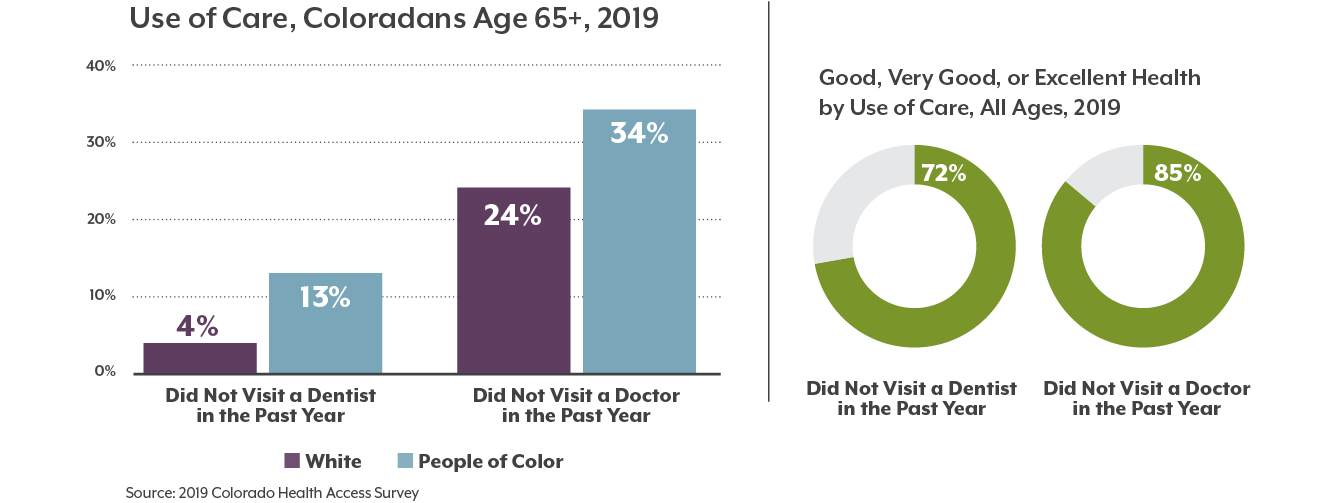

We all want to be healthy as we age, but not all Coloradans experience aging the same. Older adults who identify as a race or ethnicity other than white report worse health outcomes and greater barriers to health care and social supports.

The disproportionate number of COVID-19 infections and deaths among both older adults and people of color has been noted frequently in headlines since the spring of 2020. But less attention has been given to the intersection of these populations, older adults of color.

Older Black, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, and multiracial Coloradans are at a greater risk of dying due to health inequities, such as disproportionate rates of underlying health conditions like asthma or diabetes. A long history of discriminatory policies and racism are behind these systemic health and social inequities.

Data from the 2019 Colorado Health Access Survey lay bare the health inequities that aging Coloradans were facing prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.